Black or tarry stools

Definition

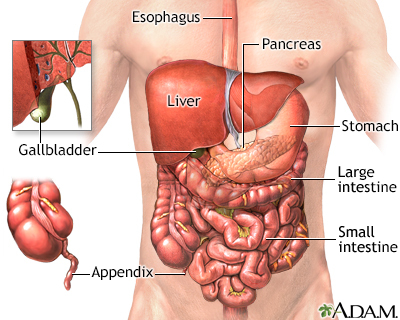

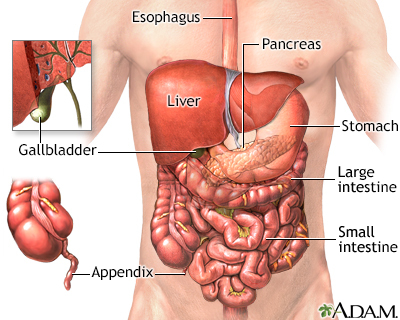

Black or tarry stools with a foul smell are a sign of a problem in the upper digestive tract. It most often indicates that there is bleeding in the stomach, small intestine, or right side of the colon.

The term melena is used to describe this finding.

Alternative Names

Stools - bloody; Melena; Stools - black or tarry; Upper gastrointestinal bleeding; Melenic stools

Considerations

Eating black licorice, blueberries, blood sausage or taking iron pills, activated charcoal, or medicines that contain bismuth (such as Pepto-Bismol), can also cause black stools. Beets and foods with red coloring can sometimes make stools appear reddish. In all these cases, your doctor can test the stool with a chemical to rule out the presence of blood.

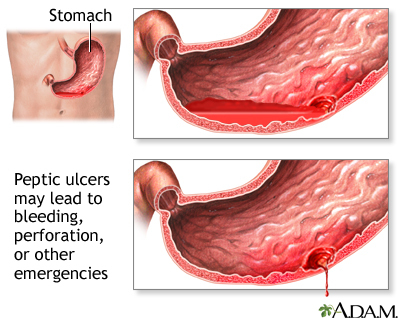

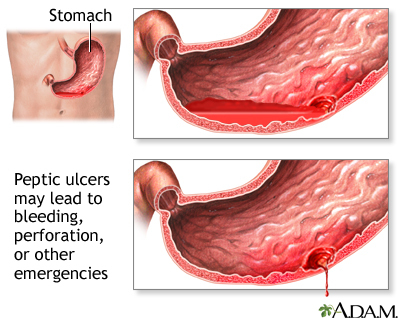

Bleeding in the esophagus or stomach (such as with peptic ulcer disease) can also cause you to vomit blood.

Causes

The color of the blood in the stools can indicate the source of bleeding.

- Black or tarry stools may be due to bleeding in the upper part of the GI (gastrointestinal) tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, or the first part of the small intestine. In this case, blood is darker because it gets digested on its way through the GI tract.

- Red or fresh blood in the stools (rectal bleeding), is a sign of bleeding from the lower GI tract (rectum and anus).

Peptic ulcers are the most common cause of acute upper GI bleeding. Black and tarry stools may also occur due to:

- Abnormal blood vessels in the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum

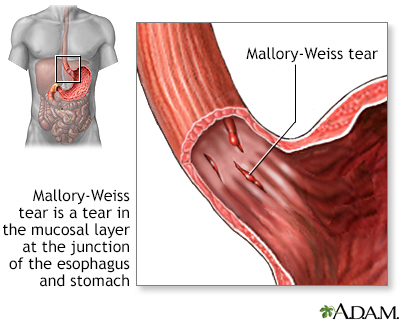

- A tear in the esophagus from violent vomiting (Mallory-Weiss tear)

- Blood supply being cut off to part of the intestines

- Inflammation of the stomach lining (gastritis)

- Trauma or foreign body

- Widened, overgrown veins (called varices) in the esophagus and stomach, commonly caused by liver cirrhosis

- Cancer of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, or ampulla of Vater

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your health care provider right away if:

- You notice blood or changes in the color of your stool

- You vomit blood

- You feel dizzy or lightheaded

In children, a small amount of blood in the stool is most often not serious. The most common cause is constipation. You should still tell your child's provider if you notice this problem.

What to Expect at Your Office Visit

Your provider will take a medical history and perform a physical exam. The exam will focus on your abdomen.

You may be asked the following questions:

- Are you taking blood thinners, such as aspirin, warfarin, Eliquis, Pradaxa, Xarelto, or clopidogrel, or similar medicines? Are you taking an NSAID, such as ibuprofen or naproxen?

- Have you had any trauma or swallowed a foreign object accidentally?

- Have you eaten black licorice, lead, Pepto-Bismol, or blueberries?

- Have you had more than one episode of blood in your stool? Is every stool this way?

- Have you lost any weight recently?

- Is there blood on the toilet paper only?

- What color is the stool?

- When did the problem develop?

- What other symptoms are present (abdominal pain, vomiting blood, bloating, excessive gas, diarrhea, or fever)?

You may need to have one or more tests to look for the cause:

- Angiography

- Bleeding scan (nuclear medicine)

- Blood studies, including a complete blood count (CBC) and differential, serum chemistries, clotting studies

- Colonoscopy

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD

- Stool culture

- Tests for the presence of Helicobacter pylori infection

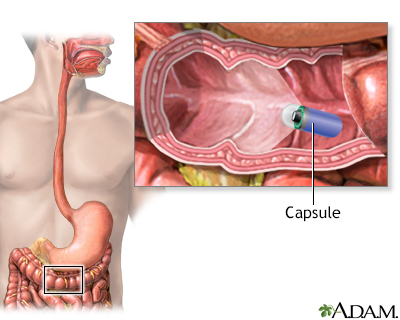

- Capsule endoscopy (a pill with a built in camera that takes a video of the small intestine)

- Double balloon enteroscopy (a scope that can reach the parts of the small intestine that are not able to be reached with EGD or colonoscopy)

Severe cases of bleeding that cause excessive blood loss and a drop in blood pressure may require surgery or hospitalization.

Gallery

References

Chaptini L, Peikin S. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Parrillo JE, Dellinger RP, eds. Critical Care Medicine: Principles of Diagnosis and Management in the Adult. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 72.

DeGeorge LM, Nable JV. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Walls RM, ed. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 26.

Kovacs TO, Jensen DM. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 126.

Savides TJ, Jensen DM. Gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 20.