Colorado tick fever

Definition

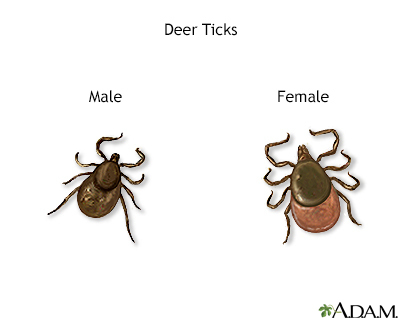

Colorado tick fever is a viral infection. It is spread by the bite of the Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni).

Alternative Names

Mountain tick fever; Mountain fever; American mountain fever

Causes

This disease is usually seen between March and September. Most cases occur in April, May, and June.

Colorado tick fever is seen most often in the western United States and Canada at elevations higher than 4,000 feet (1,219 meters). It is transmitted by a tick bite or, in very rare cases, by a blood transfusion.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Colorado tick fever most often start 1 to 14 days after the tick bite. A sudden fever continues for 3 days, goes away, then comes back 1 to 3 days later for another few days. Other symptoms include:

- Feeling weak all over and muscle aches

- Headache behind the eyes (typically during fever)

- Lethargy (sleepiness) or confusion

- Nausea and vomiting

- Rash (may be light colored)

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Skin pain

- Sweating

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will examine you and ask about your signs and symptoms. If the provider suspects you have the disease, you will also be asked about your outdoor activity.

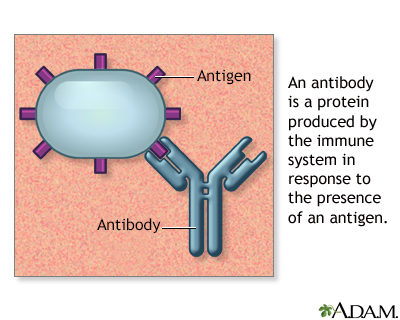

Blood tests will usually be ordered. Antibody tests can be done to confirm the infection. Other blood tests may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Liver function tests

Treatment

There are no specific treatments for this viral infection.

The provider will make sure the tick is fully removed from the skin.

You may be told to take a pain reliever if you need it. DO NOT give aspirin to a child who has the disease. Aspirin has been linked with Reye syndrome in children. It may also cause other problems in Colorado tick fever.

If complications develop, treatment will be aimed at controlling the symptoms.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Colorado tick fever usually goes away by itself and is not dangerous.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Infection of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord (meningitis)

- Irritation and swelling of the brain (encephalitis)

- Repeated bleeding episodes for no apparent cause

Call your provider if you or your child develops symptoms of this disease, if symptoms worsen or do not improve with treatment, or if new symptoms develop.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Prevention

When walking or hiking in tick-infested areas:

- Wear closed shoes

- Wear long sleeves

- Tuck long pants into socks to protect the legs

Wear light-colored clothing, which shows ticks more easily than darker colors. This makes them easier to remove.

Check yourself and your pets frequently. If you find ticks, remove them right away by using tweezers, pulling carefully and steadily. Insect repellent may be helpful.

Gallery

References

Bolgiano EB, Sexton J. Tick-borne illnesses. In: Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, eds. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 126.

Dinulos JGH. Infestations and bites. In: Dinulos JGH, ed. Habif's Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 15.

Naides SJ. Arboviruses causing fever and rash syndromes. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 358.