Caring for Those Without Health Insurance: Practical Implications of the Affordable Care Act

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), signed into law on March 23, 2010 by President Obama, was forged from a molten set of political compromises and passed by Congress along strictly partisan lines, and remains a highly charged subject whenever it is discussed. While the debate continues, implementation of the ACA will potentially impact not only the uninsured Americans who were at the heart of the law’s major provisions, but also virtually everyone else in the nation, directly or indirectly.

I prepared some material on this subject for a retired faculty group last week. As you might imagine, a lively discussion ensued! In light of the response, I concluded that this information would be of interest to the broad UF Health community. My goal in this newsletter is to provide a brief synopsis of the background leading to the law and then to focus my comments on its main objective: providing access to health insurance for the 48 million Americans who were uninsured. I will try to address the question of how successful ACA has been in reaching this objective and what problems have arisen in the process. My goal is to be factual, not political.

Setting the Stage

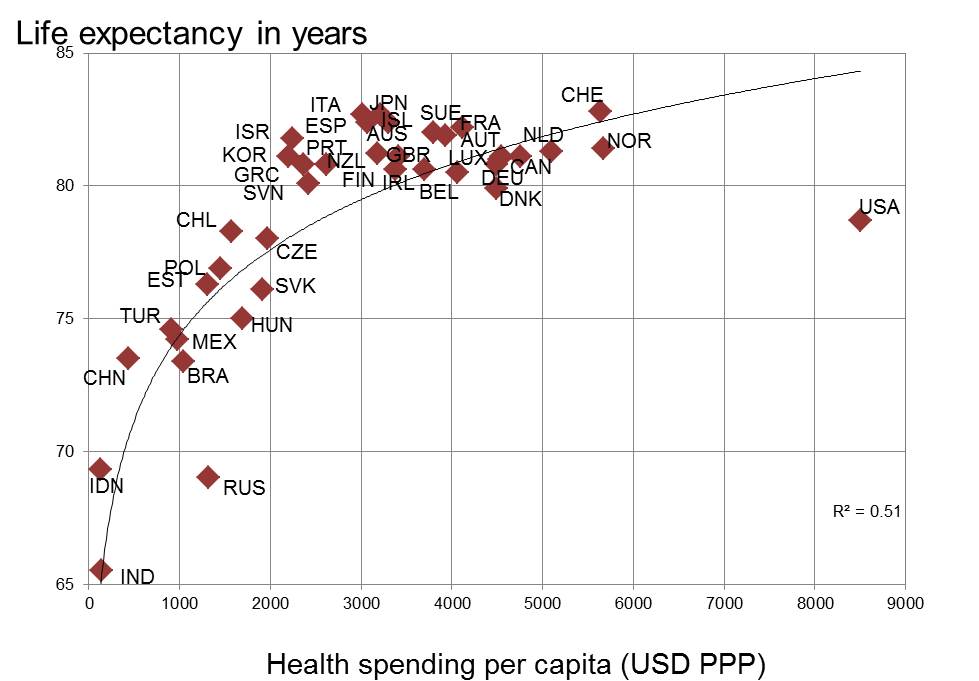

The United States does not fare well in international comparisons of cost and outcomes. In fact, we are an outlier (Figure 1). You can count 26 countries that exceed our life expectancy, and among those countries, the median health care expenditures per capita is about half of that in the United States.

Figure 1: International comparison of health status – Life expectancy in years Source: OECD Health Statistics, 2013; World Bank for non-OECD countries

For twice the per-capita expenditure on health care, we don’t do much better on a number of other outcome measures: for example, we rank 31st out of 34 developed countries in infant mortality (where the No. 1 rank is the best), 27th out of 28 in hospital admission rates for unmanaged asthma, 16th out of 19 in surgical complication rates and 12th out of 32 in heart attack fatalities.

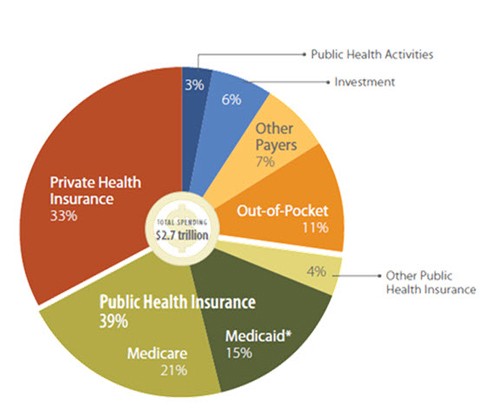

How can this be? Much of the answer lies in our unique system of paying for health care costs: as shown in Figure 2, over two-thirds of expenditures are through a patchwork of employer and government health insurance. What these expenditures have in common is that they are mostly made through a fee-for-service system in which the fees facing consumers are only a small fraction of the actual fees. As a consequence, the U.S. has become an international leader in utilization per capita, whether measured in terms of office visits, surgical procedures, imaging studies, lab tests or pharmaceuticals. Moreover, because insured patients are responsible for only a small co-pay, while the actual price is buried in the insurance premium paid primarily by employers and government, actual prices for all categories of medical care have also risen to be the highest in the world. Since total expenditure equals price times quantity, our national expenditures have increased accordingly.

Figure 2: US Health Expenditures, by Payer, 2011 Source: CMS, Office of the Actuary, National Health Expenditures, 2013 release via California Healthcare Foundation

This explains the high total cost. But what about the poor outcomes? The answer to this part of the story lies in the recognition that the pie chart shown in Figure 2 applies to the people with health insurance (and to the small percentage who pay for their care fully out of pocket). Health outcomes for these individuals approximate that of other developed countries. As noted, however, 48 million Americans had no health insurance in 2012, and the health outcomes for these individuals are much worse. Therefore, when the insured and uninsured populations are combined, the observed outcomes for life expectancy and the other conditions listed above are seen.

Who are the uninsured? They tend to be poor, working at jobs in which health insurance is not provided, and they often lack adequate income to purchase health insurance in the individual, private market. About 80 percent of families without health insurance have a family member who is employed, but about 40 percent are below the Federal Poverty Line (FPL), and another 40 percent are between the FPL and 2.5 times the FPL. Due to variations in Medicaid eligibility rules and in economic conditions, there is significant variability in uninsured rates among states. In 2012, about 4 million people in Florida did not have health insurance.

At UF Health Shands in Gainesville, about 8 percent of patients admitted to our hospital have no health insurance. At UF Health Jacksonville, the figure is 16 percent. Moreover, the percent uninsured is much higher for patients seen in our emergency rooms for medical care but not requiring admission. Overall, the actual cost to UF Health for providing this care to the uninsured is about $170 million per year.

The Affordable Care Act: Insuring the Uninsured

Although ACA has many other provisions, its main focus is to provide access to insurance among the uninsured. It does this by using the existing public and private insurance system shown in Figure 2 and creating mechanisms for individuals to gain coverage in two ways: either through Medicaid expansion (if they are below the FPL) or through subsidized health insurance premiums for new private insurance products sold in web-based health care marketplaces or “exchanges.” In the case of the exchanges, the subsidy goes down as income rises.

Overall, of the 48 million who were uninsured in 2012, it was estimated that two-thirds, or 32 million, would gain access through these two mechanisms: about 16 million through Medicaid expansion and about 16 million though the private exchanges. In addition, it was estimated that another 5 million of the uninsured between 18 and 26 years of age would gain access through their parents’ policy, another provision of ACA.

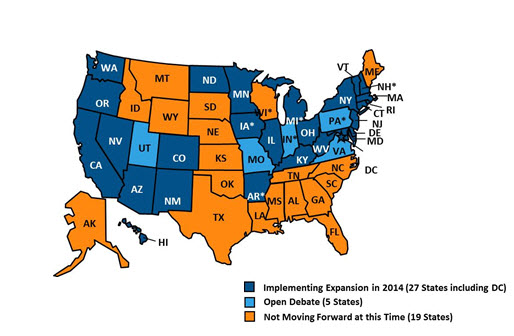

After ACA was passed by Congress, its constitutionality was challenged. On June 28, 2012, the constitutionality of the main provisions of the law was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, but the court found that individual states could decide whether to expand Medicaid to their poorest residents. The federal government would pay 100 percent of the cost of Medicaid expansion for the first three years. At that point, the state would begin to contribute a small percentage, which would top out at 10 percent by the sixth year and thereafter. In Florida, although Governor Scott supported Medicaid expansion for at least the first three years, and although the Florida Senate supported a variant of Medicaid expansion that would take advantage of the federal funding, the House Speaker opposed any form of Medicaid expansion, and therefore this part of ACA has not been implemented in Florida.

Florida is not alone. As shown in the map below (Figure 3), 24 states have not participated in Medicaid expansion. From a national perspective, of the 16 million people who were projected to be covered by Medicaid expansion, about 5 million have been covered thus far.

Figure 3: Medicaid Expansion, by State, March 2014 Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

What about coverage for the uninsured whose incomes were too high to qualify for Medicaid expansion? To cover those with incomes between 133 and 400 percent of the FPL (or between 100 and 400 percent of the FPL for states that did not expand Medicaid), ACA created health insurance marketplaces, or “exchanges,” where private insurers would offer health insurance plans from which individuals could choose. Under ACA, such plans could not exclude people with preexisting medical conditions or discriminate in other ways, and had to cover 10 essential health benefits. The rollout of the website for the exchanges was famously botched, and there were numerous other problems in the initial months of the program. Nonetheless, by the time that open enrollment for the exchanges ended, 8 million people nationally were enrolled in the exchanges — about half of the ultimate goal. Of these, about 440,000 are Floridians.

How does this work for someone who enrolls in an exchange? Let’s use the example of a 40-year-old individual in Florida whose income is 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Line ($28,725). On average across the state, based on data from the Congressional Research Service, the premium payment for the most popular plan ("silver") is $317 per month or $3,804 per year. The deductible would be, on average, $5,000. This individual would be eligible for a subsidy of $123/month or $1,476 per year on the insurance premium and federal cost sharing of $500 that would reduce the deductible to $4,500. For a family of four with two 40-year-old parents and two children, the premium would be $948 per month ($11,376 per year) with a subsidy of $553/month ($6,636/year).

Evolving Issues in ACA Implementation

It is likely that, across time, more and more uninsured people will participate in either Medicaid expansion or the exchanges, depending on their eligibility. Because the ACA was grafted onto the existing patchwork of public and private health insurance, however, with specific provisions that were the product of political compromise, several evolving issues will complicate the prospects for smooth adoption. A few examples are:

- In some communities, like Gainesville, only one insurer came forward to offer an exchange product. In general, premium prices and deductibles will be higher when there is only one (or a small handful) of insurers.

- To keep premiums low, insurers contract with a “narrow network” of physicians and hospitals. An enrollee may have seen the same doctor for many years, but that doctor may not be part of the network created by the insurer under the exchange.

- It’s easier — and more certain — for individuals to pay for health insurance through payroll deduction than by writing a check each month. Preliminary results from health insurance plans indicate that only 80 percent of people who enroll and pay for the first month’s premiums pay for the second month.

- In states like Florida that did not adopt Medicaid expansion, the most needy individuals (below 100 percent of the FPL) are not eligible for the exchanges and will remain uninsured. This is an unfortunate and ironic consequence of the Supreme Court ruling.

- Young individuals without a history of health problems may choose not to purchase health insurance, but rather add a penalty to their taxes. This may lead to adverse selection of members in the plan who are less healthy than the general population, which in turn would lead to increased premiums.

- Continued political debate will occur at every step.

What Can We Do as an Academic Health Center?

UF Health is both an educational institution and a health care provider. We can play important roles on both fronts. As the new open enrollment period begins next fall, we will engage in community-wide educational programs to provide information on eligibility for exchange products and how to enroll if eligible. As patients are seen in our faculty offices and hospitals, we will communicate to them individually about their options for exchange products if they are eligible. And as providers, we will do our best, as always, to provide excellent medical care for these newly insured individuals, who may bring longstanding medical problems that hadn’t been previously addressed because of limited access. Providing such care, as well as timely follow-up, will hopefully prevent ER visits and hospital admissions in the future for these individuals who otherwise would not see us until their condition was more advanced and acute.

Forward Together,

David S. Guzick, M.D., Ph.D. Senior Vice President for Health Affairs, UF President, UF Health

About the author