A New NIH Program Grant: UF Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center

“How do you think of translational research questions that will make a difference?” I asked Fred Moore, M.D., a professor of surgery at UF Health.

“You look at the patient,” he answered. “Understanding their clinical picture gives clues to what’s wrong and how to make it better.”

Using this patient-guided approach to research, Moore and his colleagues at UF Health have been awarded a $12 million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to create the Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center. The center, the first of its kind in the nation, reflects a partnership between Moore, who was recruited in 2011 to be chief of acute care surgery, and Lyle (“Linc”) Moldawer, Ph.D., a professor and vice chair of research in the department of surgery, along with several other colleagues at UF Health. This “P50” research center, a prestigious NIH grant mechanism in which a “spectrum of activities comprise a multidisciplinary attack on a specific disease entity or biomedical problem area,” will study long-term outcomes in patients treated for sepsis in the surgical and trauma intensive care units at UF Health Shands Hospital, with the goal of developing successful clinical interventions for sepsis and its long-term sequellae.

Sepsis is a severe combination of infection and systemic inflammation that can depress or over-activate the immune system and cause multiple organ failure. Death from sepsis was once common, but improved treatments help many people survive. Indeed, improved early recognition and consistent implementation of evidence-based guidelines have dramatically decreased the incidence of early in-hospital deaths and late multiple organ failure. Unfortunately, long-term mortality and functional recovery remain dismal for a large number of these patients, especially the aged and those who have sustained acute kidney injury. Thus, even if patients survive their acute episode of sepsis and critical illness, there are lasting repercussions that faculty in this research center will try to understand and ameliorate.

Returning to the idea of “looking at the patient” to guide research, what were the specific clinical characteristics of patients with sepsis that led to the hypotheses and aims of the research center? “We observed that many of the survivors of severe sepsis lingered in the ICU with manageable organ dysfunctions,” said Moore. “Their clinical course was characterized by recurrent inflammatory insults such as repeat operations and hospital-acquired infections, a persistent low-grade inflammation with dramatic loss of muscle mass despite optimal nutritional support, poor wound healing, and development of decubitus ulcers. These patients were commonly discharged to long-term acute care facilities with significant cognitive and functional impairments from which they rarely fully rehabilitated.”

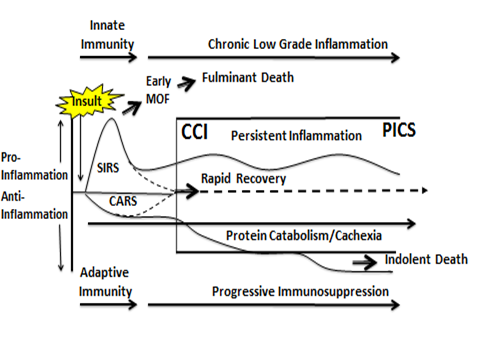

Early in his career, Dr. Moore was influenced by his older brother (also an academic surgeon), Dr. Ernest Moore at the University of Colorado, who emphasized the value of creating cartoons to describe key pathophysiologic mechanisms and how they can be studied. At Colorado, but also subsequently at UT-Houston and now at UF, younger-brother Moore followed this advice and found that cartoons could indeed crystallize the core elements of a research question. In the case of the P50 center, shown below is the cartoon that Moore and his colleagues used to take into account the key clinical characteristics of sepsis described above, and to focus attention on the central research questions that need to be answered: This cartoon depicts a new conceptual framework to describe the clinical course of patients who develop sepsis, based on recent clinical observations (by Dr. Moore) and basic immunologic discoveries (by Dr. Moldawer). In brief, a septic insult simultaneously induces an inflammatory response (called Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome or “SIRS”) and immune suppression. If SIRS is not well-managed, it can precipitate early multiple organ failure and a fulminant death trajectory. Modern ICUs prevent this progression and surviving patients either rapidly recover or enter a state of “chronic critical illness” and what Moore has coined a “persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome,” or PICS. This syndrome has become the dominant pathophysiology of chronic critical illness in surgical ICU patients, replacing multiple organ failure as the cause of prolonged ICU stays. Unfortunately, PICS typically ends in the patient’s demise, usually after repeated readmissions to a long-term acute care facility or after repeated readmissions to the hospital.

This cartoon depicts a new conceptual framework to describe the clinical course of patients who develop sepsis, based on recent clinical observations (by Dr. Moore) and basic immunologic discoveries (by Dr. Moldawer). In brief, a septic insult simultaneously induces an inflammatory response (called Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome or “SIRS”) and immune suppression. If SIRS is not well-managed, it can precipitate early multiple organ failure and a fulminant death trajectory. Modern ICUs prevent this progression and surviving patients either rapidly recover or enter a state of “chronic critical illness” and what Moore has coined a “persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome,” or PICS. This syndrome has become the dominant pathophysiology of chronic critical illness in surgical ICU patients, replacing multiple organ failure as the cause of prolonged ICU stays. Unfortunately, PICS typically ends in the patient’s demise, usually after repeated readmissions to a long-term acute care facility or after repeated readmissions to the hospital.

It was the prospect of creating a research center to address sepsis and critical illness in accordance with this framework, along with the opportunity to work with Dr. Moldawer and the strong academic infrastructure in Gainesville, that drew Moore to UF Health in 2011. Now, in a short period of time, this research team has made this dream a reality through establishment of the P50 Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center: Faculty in the center will determine the frequency, natural history and the clinical implications of PICS, will test several mechanistic hypotheses about its cause, and will develop potential and novel therapeutic interventions. There are four inter-related projects in the center, as follows:

Project 1: Epidemiology and Outcomes. Over a four-year period, the center will enroll 400 trauma and surgery ICU research participants who are newly diagnosed with sepsis, to define the incidence of CCI and determine the long-term consequences in terms of survival, functional independence and recovery. This and other center projects will draw on a central database that stores information on markers of PICS in patients’ blood, tissue and urine samples, as well as data on patients’ cognitive and physical function. The UF Institute on Aging will provide outpatient measures of physical and cognitive performance, with one year of follow-up after the initial diagnosis and treatment of sepsis.

Project 2: Bone Marrow Mechanisms. Center investigators believe that PICS is a myelodysplastic disease, implying failure of the bone marrow in its normal production of healthy white blood cells. In particular, the hypothesis tested in Project 2 is that sepsis induces expansion of immature myeloid-derived suppressor cells, or MDSCs, from the bone marrow, contributing directly to the persistent inflammation, immunosuppression and catabolism often seen in these patients. This project will be led by Dr. Moldawer, along with Philip Efron, M.D., an assistant professor of surgery and anesthesiology, and Christiaan Leeuwenburgh, Ph.D., a professor and chief of the division of biology of aging in the UF department of aging and geriatric research. Dr. Moldawer sums up the novelty of this hypothesis: “The potential role of MDSCs in the pathogenesis of PICS challenges current dogma surrounding this population of cells, and suggests that the simultaneous inflammation and immune suppression in these patients is actually a beneficial host response that has gone awry”.

Project 3. Angiogenic Balance. It is also hypothesized that acute kidney injury promotes an imbalance in the angiogenic response to sepsis, and that this drives the expansion of immature myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Understanding this phenomenon is potentially important, as early kidney injury fosters chronic kidney dysfunction, which in itself has both inflammatory and muscle-wasting consequences. Project 3 will be led by Mark Segal, M.D., Ph.D., professor and chief of the UF department of medicine’s division of nephrology, hypertension and renal transplantation, and Azra Bihorac, M.D., M.S., an associate professor of anesthesiology, medicine and surgery. As explained by Dr. Segal: “This project brings together our basic science observation concerning the ability of kidney-derived erythropoietin to stimulate anti-angiogenesis and our clinical observation that those septic patients with anti-angiogenic imbalance have poorer survival, in a hypothesis that can be tested: ‘Is the level of kidney derived erythropoietin a key determinate of long-term prognosis?’ In addition, critically ill patients lose muscle mass very rapidly and thus their true level of kidney dysfunction is often not appreciated, and chronic kidney disease itself is associated with inflammation, immunosuppression, catabolism (equivalent to PICS) and increased morbidity.”

Project 4: Clinical Intervention. Based on the idea that the bed rest and mechanical ventilator support common to critically ill patients contribute to the inflammatory and muscle-wasting consequences of the condition, a clinical trial will be conducted to test the hypothesis that a resistance exercise program can reduce muscle wasting and inflammation and improve muscle function. This project will be led by A. Daniel Martin, Ph.D., P.T., a professor in the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions’ department of physical therapy, and will also involve Dr. Leeuwenburgh and several other researchers. “We believe that muscle weakness, inactivity and ventilator dependence fuels a vicious cycle of inflammation, immunosuppression and hospital-related complications,” explained Leeuwenburgh. “Dr. Martin and I will determine whether clinically practical rehabilitation techniques — administered at the patient’s bedside — can improve diaphragm and lower-limb muscle strength, and examine whether strength training can interfere with the vicious cycle of inactivity, inflammation and protein catabolism in these patients.”

To support these four projects, the Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center comprises, in addition to an Administration Core, a Human Subjects Core that will be responsible for the screening, consenting, documenting in-hospital clinical course and obtaining blood and urine samples at set intervals of the enrolled septic surgical ICU patients. Working closely with the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, the center’s Data Management and Biostatistics Core has already pioneered development and implementation of the center’s electronic case report form and database which will be auto-populated from the UF Health electronic medical record. A Bioanalytics Core will centralize analyses of blood, urine and skeletal muscle tissue to improve efficiency, standardize analyses and reduce costs. And an Animal Studies Core will provide the program with a standardized model of murine PICS induced by surgical sepsis for pre-clinical interventional studies.

This P50 research center represents the culmination of decades of work for Drs. Moore and Moldawer, reflects the welcoming and collaborative environment for translational science that we have tried to foster at UF Health, and most importantly, will no doubt lead to much improved long-term outcomes for the many patients who develop sepsis and suffer from critical illness. Moore sums it up this way: “We’re going to focus this diverse knowledge and expertise to solve what is going to become a much bigger problem as we move forward, because sepsis is really a disease of the elderly. We’re beginning to recognize that sepsis has a very high rate of recidivism — people get it, they get it again and then they get it again; and then they’re dead. Our ultimate goal is to understand how patients get into this futile trajectory. We believe PICS is the next challenging horizon in surgical critical care, and are focusing our research efforts to develop novel interventions to prevent it.”

Forward Together,

David S. Guzick, M.D., Ph.D.

Senior Vice President for Health Affairs, UF

President, UF Health

About the author