Hormone released during exercise can boost heart function, researchers find

Here’s another reason to work out: A hormone released during exercise helps the heart function better.

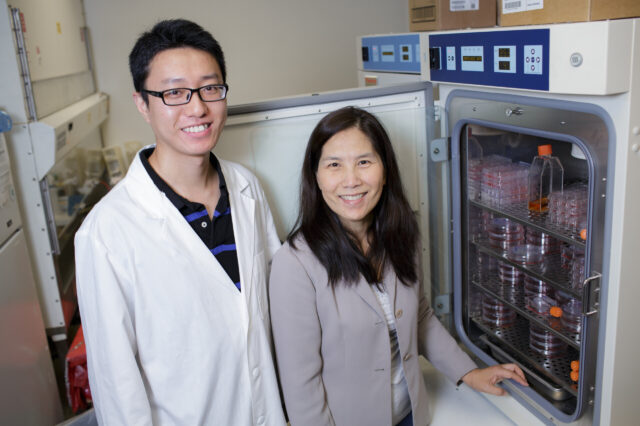

That’s what a group that includes UF Health researchers found after studying how cells and mouse models were affected by irisin, a hormone that surges when the heart and other muscles are exerted. The findings, published Aug. 25 in the journal PLOS One, show that irisin drives a number of positive effects on the heart, said Li-Jun Yang, M.D., a professor of hematopathology in the UF College of Medicine’s department of pathology, immunology and laboratory medicine.

“It makes the heart work better by creating more oxygen consumption and energy consumption. That’s the major result at the cellular level,” Yang said.

The latest findings are yet another development in irisin’s short, controversial history. Irisin was hailed for its fat-burning ability after Harvard Medical School researchers discovered it in 2012, though its existence was challenged by some scientists. Earlier this month, scientists who did an unrelated study at the Boston-based Dana-Farber Cancer Institute confirmed its existence. In May 2014, Yang and other UF Health researchers discovered a way to create a stable protein form of irisin that made obese mice lose weight without exercising, raising the possibility of a future treatment for obesity and Type 2 diabetes in humans.

In the present study, Yang’s group uncovered new details about the way irisin affects the heart. They found that irisin elevated levels of calcium within cells, which is critical for heart contractions. When tested in heart cells from a rat model, a low dose of irisin quadrupled the cells’ calcium level.

Irisin also increased metabolism in mitochondria, the part of a cell that supplies energy for a variety of heart functions, researchers determined. Additionally, the researchers found that treating mice with irisin activated multiple cellular signaling paths in cardiac muscle that are crucial for heart health.

All of that points to irisin being beneficial for overall heart function, Yang said.

“We know that increased calcium and cellular metabolism make the heart work better. When your heart is working better, you feel better,” she said.

For now, exercise is the easiest way to stimulate irisin’s beneficial effects, though the study did not determine how much exertion is needed to benefit the heart. Irisin might also be used someday as a drug for people who are unable to exercise, Yang said. Before that could happen, scientists would have to find a way to target specific cellular signaling that would mimic the effects of exercise.

Beyond its heart-helping abilities, Yang’s group showed in a previous study that the hormone induced weight loss in obese mice. Researchers believe irisin does that by binding to fat cells and helping to convert energy-storing white fat cells into energy-burning brown fat cells.

Next, Yang said she would like to obtain funding that would allow further study of irisin’s effects in mouse models. Irisin’s effects on heart functions have yet to be tested in humans.

The current research was a collaboration with Yousong Ding, Ph.D., an assistant professor of medicinal chemistry at the UF College of Pharmacy; the veterinary medical school at Louisiana State University; and the Center for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine in China. Chao Xie, a research assistant in Yang’s laboratory, was the first author of the paper.

About the author