Gene therapy improves daylight vision, color vision deficiencies in animal model

For people with blue cone monochromacy, the world is blurry, colorless and uncomfortably bright. Now, University of Florida Health researchers have found a gene therapy that restored crucial visual functions to affected cone photoreceptor cells during testing in mice.

While additional study is needed, researchers say the findings are proof of concept that the gene therapy works in an animal model and should be considered for a human clinical trial. The findings were published recently in the journal Molecular Vision.

The disease affects about 1 in every 100,000 people, almost all of them males. It is caused by defective genes that affect red and green cone photoreceptors in the retina, leaving patients with only blue color receptors.

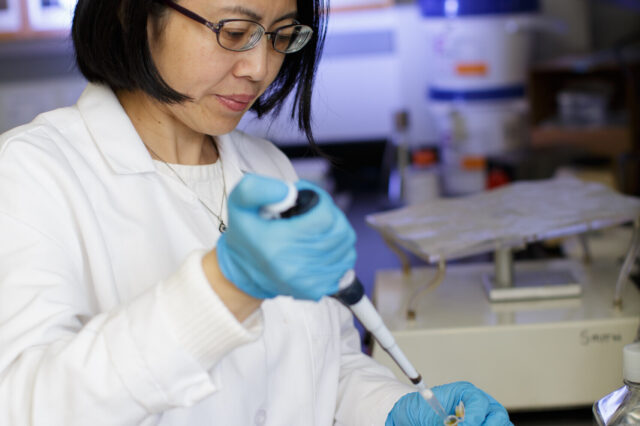

“The children who have this disorder are born with very poor visual acuity. They cannot see color. This is a very devastating disease,” said Wen-Tao Deng, Ph.D., an assistant scientist in the UF College of Medicine’s department of ophthalmology research.

To establish their findings, the researchers used a harmless adeno-associated virus to deliver human genes into mutant mouse retinas with defective cone function and color vision. The gene therapy works by stimulating the production of crucial proteins known as opsins. The proteins are expressed by the remaining viable cell bodies, promoting regeneration of the outer segments of so-called M-cone cells that are responsible for cone function and color vision in mice, the researchers found.

Six weeks after being treated with one of two human opsin proteins, the mice were given an eye test called electroretinography to detect abnormal retina function. The treatment restored cone electroretinography in up to 70 percent of the mice with normal vision, the researchers found. The gene therapy also appears to be durable: Seven months after treatment, the beneficial effects on vison were still present.

The findings are “solid evidence” that human opsin proteins can be used to restore daylight vision and color vision in otherwise nonfunctional cone cells, the researchers concluded. That makes the gene therapy a potential candidate for treating blue cone monochromacy in humans, they said.

“We functionally and structurally restored normal vision in the mice by restoring their cones,” said Deng.

While the gene therapy shows promise for humans, it also poses some challenges for researchers. Since most patients have never experienced full-color vision before, Deng said it’s not clear how their brain’s visual cortex will respond to new inputs. Prior testing in monkeys that were born with red-green color vision deficiency found they were able to distinguish those colors after the gene therapy treatment. That suggests the human brain might adapt to gene-driven changes in color vision, Deng said.

Another challenge will be developing a “high penetration” vector to deliver the gene therapy. The current delivery method involves detaching the retina, which Deng said is not an ideal approach because it can potentially damage the fovea, a small depression in the retina where the center of the field of vision is focused.

Still, researchers said the findings clearly establish that the gene therapy induces production of crucial proteins that can rescue the function of the cone cells. That makes the technique worthy of moving toward trials in human patients, they said.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Research to Prevent Blindness, the BCM Families Foundation and the Macula Vision Research Foundation.

About the author