UF researcher finds link between common food poison toxin and colorectal cancer

University of Florida researchers have found a link between colorectal cancer in mice and the most commonly reported bacterial cause of food poisoning in the United States.

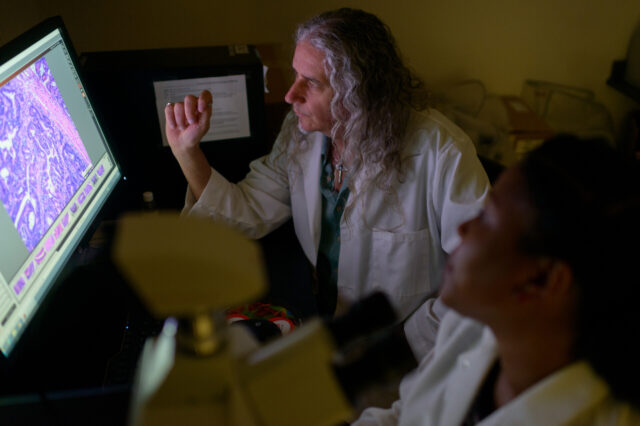

Little is known about Campylobacter jejuni, a bacteria that most commonly causes diarrheal illness, or its effect on cancer, said Christian Jobin, Ph.D., senior author and a professor of medicine in the UF College of Medicine. However, it isn’t a rare bacterium — around 2 million cases of human campylobacteriosis ranging from loose stools to dysentery occur each year in the United States.

The study was published in the journal Gut this month and is featured as its cover story.

“Some Campylobacter jejuni species have a toxin called cytolethal distending toxin, or CDT,” Jobin said. “We demonstrated that this CDT toxin from the Campylobacter jejuni is essential to causing colorectal cancer in mice.”

Previously, researchers were just looking at how Campylobacter jejuni impacts intestinal inflammation, he said, because it was known that C. jejuni may cause relapse in inflammatory bowel disease.

“Inflammation is some sort of a fuel for cancer,” said Jobin, who is also the co-program leader of the UF Health Cancer Center’s Cancer and Therapeutics and Host Response research program. “Our study from 10 years ago eventually evolved to focus on cancer because of the cancer risk associated with inflammation.”

Persistent inflammation presents a greater risk for cancer, Jobin said. For example, patients with inflammatory bowel disease are more likely to develop colorectal cancer due to constant inflammation.

One of the key findings of Jobin’s current cancer study is that using inflammatory inhibitors in a mouse model prevented both inflammation and cancer, suggesting the capability to manipulate cancer-causing activity of C. jejuni.

It’s possible that carrying C. jejuni may also put humans at higher risk of cancer, Jobin said. Researchers now need to look at the prevalence of CDT and if it is associated with cancer development in humans.

The study also found no association between microbiota composition, the collective assembly of microorganisms that live in the gut, and cancer development, he said.

In recent years, researchers have observed that intestinal microbiota composition of patients with colorectal cancer is different than healthy subjects, leading to the theory that reversing microbiota changes may prevent the development of cancer. The gut microbiome is an important aspect of a person’s health — it helps with digestion and benefits the immune system. These new findings show that changes to the microbiota made by C. jejuni infection had no effect on the development of colorectal cancer in mouse models.

“Our study shows that even if toxin-deficient C. jejuni change the microbiota composition, these changes were dissociated from colorectal development, which means that the CDT alone was able to drive the cancer and not the change of the microbiota,” Jobin said.

About the author