For UF researchers, pausing and resuming work has brought major challenges, sparked innovation

Media contact: Ken Garcia at kdgarcia@ufl.edu or 352-273-9799

David P. Norton, Ph.D., has spent nearly a decade building a collaborative, leading-edge research environment at the University of Florida. But as the number of coronavirus cases began to swell in Florida this spring, Norton and his leadership colleagues faced a daunting challenge: how to pause — and then restart — research at UF’s 16 colleges in Gainesville and dozens of facilities statewide.

For Norton, UF’s vice president for research, March was a blur of complicated questions and big decisions. What kinds of research activities needed to, and could, continue? How could more than 4,000 students, faculty, staff and postdoctoral associates stay engaged and productive? How can valuable scientific work in progress be preserved?

The issues ranged from minute to massive: maintaining freezers filled with scientific samples, preserving cell lines, deciding how to handle ongoing human clinical trials and managing a large-scale migration to remote work.

“We paused a $900 million research operation,” he said. “It’s been an extreme challenge but one that we have been able to manage.”

In recent weeks, researchers have begun returning to campus in a gradual and deliberate manner. Everyone has been tested for the coronavirus under UF’s Screen, Test & Protect program. UF has entered Stage 3 of its four-stage Research Resumption Plan. Stage 3 emphasizes physical distancing, face covering and continuing a steady return to scientific activity while gradually increasing the occupancy limits in labs and offices. Some labs have implemented staggered work shifts to keep occupancy low.

The unprecedented shutdown of the research engine that drives the state’s flagship university sparked a different kind of innovation as creativity and novel approaches flourished across campus. Hundeds of researchers took aim at COVID-19. Lab time was replaced with other scientific and instructional work. There was even a competition among researchers to pitch out-of-the-box ideas modeled after the popular TV show “Shark Tank.’’

“Most people were able to pivot to get important things done when they couldn’t be in a lab,” Norton said. By mid-May, research activity was about 50% of what it had been before Florida’s stay-at-home order took effect, he said.

Still, some tasks had to be put on hold. “Wet bench” activity, the day-to-day work done in biomedical and some other research labs, was halted. So was engineering research that required precision measurements and sophisticated equipment. In some cases, months of research work were lost during the shutdown and will have to be repeated or restarted, according to Norton.

“While some of our research pursuits continued, the bench laboratory activities have suffered significantly during the pandemic,” he told research faculty and staff in mid-May.

Other activities were deemed too crucial to be paused. A clinical trial involving brain cancer research kept going, but not before carefully considering the safety of both research workers and study participants. Ultimately, it was decided that stopping the trial would be potentially detrimental to its participants.

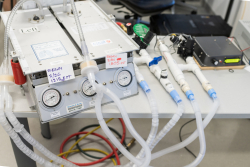

One bright spot amid the research pause was the creativity shown by UF’s researchers, Norton said. UF Health anesthesiologists teamed up with engineering researchers to create a ventilator with hardware store parts. A team of anesthesiologists and wind-engineering experts devised economical face shields and makeshift intubation technology. A potential COVID-19 vaccine that uses gene therapy techniques pioneered at UF is being studied. Other researchers devised a way to use 3D printing to quickly produce nasal swabs for COVID-19 testing.

Meanwhile, the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, or CTSI, and the Office of the Senior Vice President for Health Affairs, set up a $2 million pilot research fund for scientists with translational projects that can be rapidly mobilized into clinical trials. The initial 19 projects to receive funding include studying existing antiviral medications for effectiveness against COVID-19 and a novel approach to induce rapid healing in critical-care COVID-19 patients.

Across campus, nearly 200 COVID-19-related research projects were underway as of late June.

“A large university like ours has a lot of expertise and a true desire to make a positive impact,” Norton said. “It has been a real coming together for the community. It was, without question, one of the most encouraging parts of the pandemic.”

“A large university like ours has a lot of expertise and a true desire to make a positive impact,” Norton said. “It has been a real coming together for the community. It was, without question, one of the most encouraging parts of the pandemic.”

For researchers, pausing their lab work was uncharted territory. Jay McLaughlin, Ph.D., a pharmacodynamics professor in the College of Pharmacy, studies how pharmaceuticals can be used to treat brain disease. When it became evident in late March that most research would be halted, McLaughlin’s lab went into high gear. At the time, he had six research projects in progress and a Ph.D. candidate who was defending a thesis.

“We upped the tempo. We had staff working around the clock to complete useful findings before we vacated the lab,” he said.

While some experiments had to be ended without viable results, McLaughlin said the losses were mitigated by the work acceleration. When his lab went dark, McLauglin and his core group of about 12 students and researchers shifted their focus. Four graduate students dug into their thesis work. McLaughlin tended to his writing, working on grant applications and papers for scientific journals.

“Everyone hit the keyboards. It was time to write papers,” he said.

Yet, it wasn’t all smooth and easy. When an editor at a scientific journal asked for additional experiments to be conducted, McLaughlin asked for — and got — permission to do limited lab work. Ultimately, that flexibility provided the data needed to publish two scientific papers.

The research pause also gave McLaughlin room to think about the art of being a professor. There was time to consider ways to improve his classes and teaching methods. Mentoring his students felt a little more relaxed. While the situation wasn’t ideal, McLaughlin said his lab made the most of it. He has published six scientific papers this year, with more on the way. Much of his research was kept intact and there was also time to think about improving his work, something he called “restorative disruption.”

“My job is to teach students so they can go off and do amazing things,” he said. “This was an opportunity to try to double down on that.”

The lab closures also provided a spark for new approaches and dormant ideas, said Duane Mitchell, M.D., Ph.D., the director of the CTSI and co-director of the Preston A. Wells, Jr. Center for Brain Tumor Therapy.

Mitchell and his colleagues launched a “Shark Tank”-style competition modeled after the business reality television series that launches entrepreneurial ideas. Students, faculty and fellows were encouraged to pitch scientific ideas that they hadn’t been able to start before the pandemic.

Among the ideas that surfaced was a new way to identify COVID-19 therapeutic targets with the goal of contributing to a broader, more effective vaccine. Mitchell, a brain tumor immunotherapy researcher, also challenged research colleagues to think about the best ways to use their time while the labs went dark. That, Mitchell said, raised the breadth of proficiency in “dry lab” skills such as large and complex data analyses and use of computer modeling.

The CTSI also convened a COVID-19 task force, chaired by Mitchell, to organize and catalyze COVID-19-related clinical and translational research, adaptations in education and training, and maintenance of community outreach and engagement during the pandemic. A CTSI database now tracks COVID-19 research across campus, which has grown to over 300 submissions to the Institutional Review Board and greater than 250 COVID-19 focused grant proposals from UF scientists.

Mitchell said he has never seen so many researchers from diverse disciplines simultaneously interested in solving one issue.

“The creativity and ideas that our researchers have brought forward to address this threat have been impressive,” he said. “It’s been a remarkable response — not just focused on treating or preventing the disease, but also efforts to reduce the lasting effects of the pandemic on the population.”

Still, resuming a large research enterprise comes with its own novel challenges.

“We needed to bring back the full structure of scientific research, patient care and community engagement, but do it in a way that reduces risks and is still effective,” Mitchell said. “Everyone has had to adapt to that in a very short period of time.”

For McLaughlin, the College of Pharmacy researcher, it has meant changes large and small. More lab meetings are held on Zoom. Everyone is particularly vigilant about cleaning and personal protective equipment, he said.

For Norton, the pandemic has been a paradigm shift.

“The challenge for us is to rethink how we do research in the age of coronavirus,” he said.

Yet one thing is a constant: the urgency and restlessness that fuels scientific discovery.

“Almost from the moment that research was paused, everyone was eager to get back to the labs,” Norton said.

About the author