Experts outline global operational and research path to address emerging COVID-19 viral variants

As COVID-19 vaccinations continue to be administered around the world, a coordinated global response to viral variants that may threaten the protection provided by vaccines is critical, writes a group of World Health Organization scientists, including the University of Florida’s Ira Longini, Ph.D., in a special report published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

In India, a “double mutant” viral variant appears to have driven a surge of COVID-19 infection this spring with new reported cases numbering more than 300,000 a day in May.

“The variant of concern in India, known as delta, has mutations that make the virus possibly more transmissible, and antibodies due to past infections and current vaccines could be less protective against it. These characteristics, among other factors, may have contributed to the massive epidemic in India,” said Longini, a professor of biostatistics in the UF College of Public Health and Health Professions and the UF College of Medicine. “As this virus spreads to other parts of the world, there may be concerns that current vaccines may be less effective, at least against infection.”

A variant overwhelming Brazil and spreading across the Americas called gamma affects immune escape, meaning people who have already had COVID-19 are more susceptible to reinfection. Current vaccines also could be somewhat less effective against gamma, said Longini, a member of UF’s Emerging Pathogens Institute.

The authors, who are members and advisers of the expert group for the WHO Solidarity Trial, an international clinical trial testing COVID-19 treatments and vaccines, outline four priorities for a coordinated response to variants. These include global strategies to determine whether existing vaccines are losing efficacy against variants; decisions on the need for modified or new vaccines to restore efficacy against variants; efforts to reduce the likelihood that viral variants of concern will emerge; and international coordination of research and response to new variants, led by WHO.

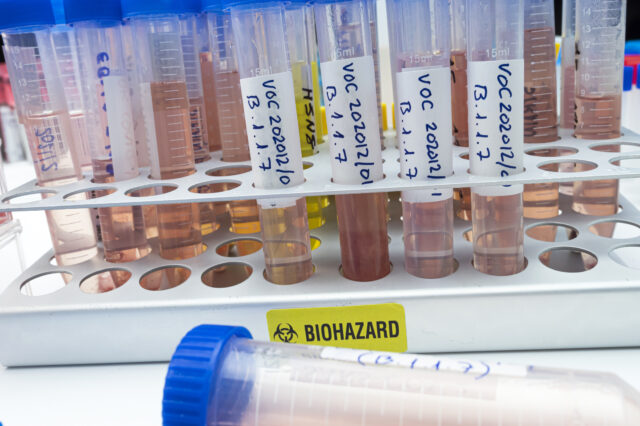

The discovery and tracking of variants depends on the ability to carry out genetic sequencing on sample COVID-19 tests that use polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, technology, Longini said.

“There is quite a bit of variation on the extent of sequencing in the surveillance systems by country,” he said. “For example, there has been extensive sequencing in the U.K., somewhat spotty sequencing in the U.S., and almost no sequencing at all in many countries.”

WHO has been tracking the emergence of viral variants since early in the pandemic and recommends that all countries increase the collection of samples for sequencing and share these with one another through the use of public databases. In their article, the WHO authors describe a number of clinical trial approaches to help determine the efficacy of current vaccines against new variants. Now is the time to plan for the development of new vaccines that are effective against emerging variants, are single-dose, are more easily scalable for production and do not require a temperature-controlled supply chain, they write.

“We will almost certainly eventually need to give already vaccinated people booster doses of vaccine containing spike protein that can neutralize many of the circulating viral types going into the future,” Longini said. “This could take the form of a yearly dose of vaccine, much as we currently do for seasonal influenza.”

To limit the appearance of new variants, the researchers suggest strategies such as continuing public health measures, including masking, physical distancing and vaccinations to reduce transmission; avoiding unproven vaccines and treatments; and considering targeted vaccination approaches to reduce community transmission.

Finally, research coordination at the global level is key for maintaining vaccine efficacy against variants as well as ensuring equitable access to vaccines.

“In order to slow the emergence and transmission of COVID-19 variants, we need to slow transmission of the virus in general as much as possible,” Longini said. “This could best be achieved by providing vaccine to the countries of the world that need it the most, and not just concentrating vaccine in the rich countries.”

Media contact: Ken Garcia at kdgarcia@ufl.edu or 352-265-9408.

About the author