Ehrlichiosis

Definition

Ehrlichiosis is a bacterial infection transmitted by the bite of a tick.

Alternative Names

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis; HME; Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis; HGE; Human granulocytic anaplasmosis; HGA

Causes

Ehrlichiosis is caused by bacteria that belong to the family called rickettsiae. Rickettsial bacteria cause a number of serious diseases worldwide, including Rocky Mountain spotted fever and typhus. All of these diseases are spread to humans by a tick, flea, or mite bite.

Scientists first described ehrlichiosis in 1990. There are two types of the disease in the United States:

- Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) is caused by the rickettsial bacteria Ehrlichia chaffeensis.

- Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is also called human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA). It is caused by the rickettsial bacteria called Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

Ehrlichia bacteria can be carried by the:

- American dog tick

- Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis), which can also cause Lyme disease

- Lone Star tick

In the United States, HME is found mainly in the southern central states and the Southeast. HGE is found mainly in the Northeast and upper Midwest.

Risk factors for ehrlichiosis include:

- Living near an area with a lot of ticks

- Owning a pet that may bring a tick home

- Walking or playing in high grasses

Symptoms

The incubation period between the tick bite and when symptoms occur is about 7 to 14 days.

Symptoms may seem like the flu (influenza), and may include:

- Fever and chills

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Nausea

Other possible symptoms:

- Diarrhea

- Fine pinhead-sized areas of bleeding into the skin (petechial rash)

- Flat red rash (maculopapular rash), which is uncommon

- General ill feeling (malaise)

A rash appears in fewer than one third of cases. Sometimes, the disease may be mistaken for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, if the rash is present. The symptoms are often mild, but people are sometimes sick enough to see a health care provider.

Exams and Tests

The provider will do a physical exam and check your vital signs, including:

- Blood pressure

- Heart rate

- Temperature

Other tests include:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Granulocyte stain

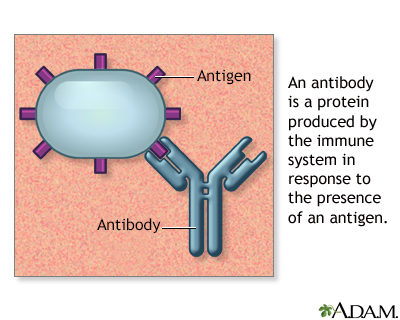

- Indirect fluorescent antibody test

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood sample

Treatment

Antibiotics (tetracycline or doxycycline) are used to treat the disease. Children should not take tetracycline by mouth until after all their permanent teeth have grown in, because it can permanently change the color of growing teeth. Doxycycline that is used for 2 weeks or less usually does not discolor a child's permanent teeth. Rifampin has also been used in people who cannot tolerate doxycycline.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Ehrlichiosis is rarely deadly. With antibiotics, people usually improve within 24 to 48 hours. Recovery may take up to 3 weeks.

Possible Complications

Untreated, this infection may lead to:

- Coma

- Death (rare)

- Kidney damage

- Lung damage

- Other organ damage

- Seizure

In rare cases, a tick bite can lead to more than one infection (co-infection). This is because ticks can carry more than one type of organism. Two such co-infections are:

- Lyme disease

- Babesiosis, a parasitic disease similar to malaria

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you become sick after a recent tick bite or if you have been in areas where ticks are common. Be sure to tell your provider about the tick exposure.

Prevention

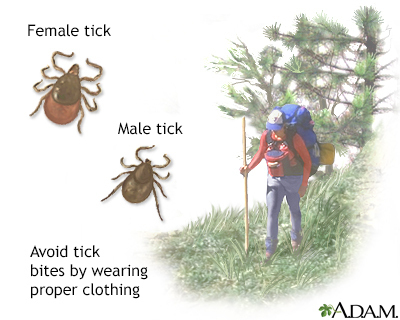

Ehrlichiosis is spread by tick bites. Measures should be taken to prevent tick bites, including:

- Wear long pants and long sleeves when walking through heavy brush, tall grass, and thickly wooded areas.

- Pull your socks over the outside of pants to prevent ticks from crawling up your leg.

- Keep your shirt tucked into your pants.

- Wear light-colored clothes so that ticks can be spotted easily.

- Spray your clothes with insect repellent.

- Check your clothes and skin often while in the woods.

After returning home:

- Remove your clothes. Look closely at all skin surfaces, including scalp. Ticks can quickly climb up the length of body.

- Some ticks are large and easy to locate. Other ticks can be quite small, so carefully look at all black or brown spots on the skin.

- If possible, ask someone to help you examine your body for ticks.

- An adult should examine children carefully.

Studies suggest that a tick must be attached to your body for at least 24 hours to cause disease. Early removal may prevent infection.

If you are bitten by a tick, write down the date and time the bite happened. Bring this information, along with the tick (if possible), to your provider if you become sick.

Gallery

References

Dumler JS, Walker DH. Ehrlichia chaffeensis (human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis), Anaplasma phagocytophilum (human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis), and other anaplasmataceae. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 192.

Fournier PE, Raoult D. Rickettsial infections. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 311.