Osgood-Schlatter disease

Definition

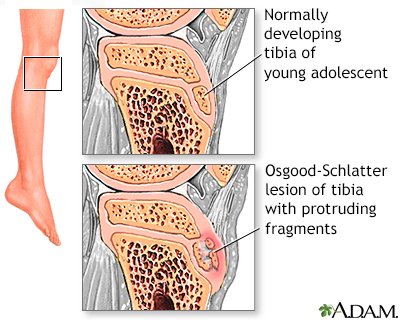

Osgood-Schlatter disease is a painful swelling of the bump on the upper part of the shinbone, just below the knee. This bump is called the anterior tibial tubercle.

Alternative Names

Osteochondrosis; Knee pain - Osgood-Schlatter

Causes

Osgood-Schlatter disease is thought to be caused by small injuries to the knee area from overuse before the knee is finished growing.

The quadriceps muscle is a large, strong muscle on the front part of the upper leg. When this muscle squeezes (contracts), it straightens the knee. The quadriceps muscle is an important muscle for running, jumping, and climbing.

When the quadriceps muscle is used a lot in sports activities during a child's growth spurt, this area becomes irritated or swollen and causes pain.

It is common in adolescents who play soccer, basketball, and volleyball, and who participate in gymnastics. Osgood-Schlatter disease affects more boys than girls.

Symptoms

The main symptom is painful swelling over a bump on the lower leg bone (shinbone). Symptoms occur on one or both legs.

You may have leg pain or knee pain, which gets worse with running, jumping, and climbing stairs.

The area is tender to pressure, and swelling ranges from mild to severe.

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider can tell if you have this condition by doing a physical exam.

A bone x-ray may be normal, or it may show swelling or damage to the tibial tubercle. This is a bony bump below the knee. X-rays are rarely used unless the provider wants to rule out other causes of the pain.

Treatment

Osgood-Schlatter disease will almost always go away on its own once the child stops growing.

Treatment includes:

- Resting the knee and decreasing activity when symptoms develop

- Putting ice over the painful area 2 to 4 times a day, and after activities

- Taking ibuprofen or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or acetaminophen (Tylenol)

In many cases, the condition will get better using these methods.

Adolescents may play sports if the activity does not cause too much pain. However, symptoms will get better faster when activity is limited. Sometimes, a child will need to take a break from most or all sports for 2 or more months.

Rarely, a cast or brace may be used to support the leg until it heals if symptoms do not go away. This most often takes 6 to 8 weeks. Crutches may be used for walking to keep weight off the painful leg.

Surgery may be needed in rare cases.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Most cases get better on their own after a few weeks or months. Most cases go away once the child finished growing.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your provider if your child has knee or leg pain, or if pain does not get better with treatment.

Prevention

The small injuries that may cause this disorder often go unnoticed, so prevention may not be possible. Regular stretching, both before and after exercise and athletics, can help prevent injury.

Gallery

References

Lawrence JTR. The knee. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 697.

Milewski MD, Wylie J, Nissen CW, Prokop TR. Knee injuries in skeletally immature athletes. In: Miller MD, Thompson SR, eds. DeLee, Drez, & Miller's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 137.

Sheffer BW. Osteochondrosis or epiphysitis and other miscellaneous affections. In: Azar FM, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 32.