Skin turgor

Definition

Skin turgor is the skin's elasticity. It is the ability of skin to change shape and return to normal.

Alternative Names

Doughy skin; Poor skin turgor; Good skin turgor; Decreased skin turgor

Considerations

Skin turgor is a sign of fluid loss (dehydration). Diarrhea or vomiting can cause fluid loss. Infants and young children with these conditions can rapidly lose a lot of fluid, if they do not take enough water. Fever speeds up this process.

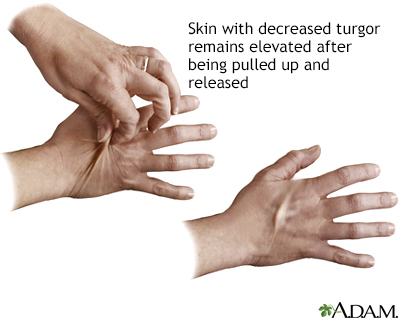

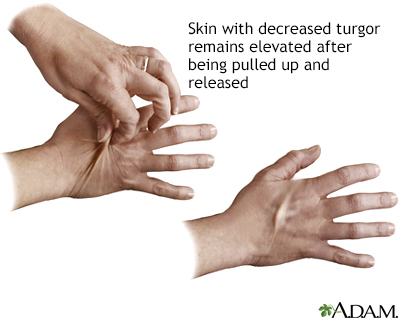

To check for skin turgor, the health care provider grasps the skin between two fingers so that it is tented up. Commonly on the lower arm or abdomen is checked. The skin is held for a few seconds then released.

Skin with normal turgor snaps rapidly back to its normal position. Skin with poor turgor takes time to return to its normal position.

Lack of skin turgor occurs with moderate to severe fluid loss. Mild dehydration is when fluid loss equals 5% of body weight. Moderate dehydration is 10% loss and severe dehydration is 15% or more loss of body weight.

Edema is a condition where fluid builds up in the tissues and causes swelling. This causes the skin to be extremely difficult to pinch up.

Causes

Common causes of poor skin turgor are:

- Decreased fluid intake

- Dehydration

- Diarrhea

- Diabetes

- Extreme weight loss

- Heat exhaustion (excessive sweating without enough fluid intake)

- Vomiting

Connective tissue disorders such as scleroderma and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome can affect the elasticity of the skin, but this is not related to the amount of fluid in the body.

Home Care

You can quickly check for dehydration at home. Pinch the skin over the back of the hand, on the abdomen, or over the front of the chest under the collarbone. This will show skin turgor.

Mild dehydration will cause the skin to be slightly slow in its return to normal. To rehydrate, drink more fluids -- particularly water.

Severe turgor indicates moderate or severe fluid loss. See your provider right away.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if:

- Poor skin turgor occurs with vomiting, diarrhea, or fever.

- The skin is very slow to return to normal, or the skin "tents" up during a check. This can indicate severe dehydration that needs quick treatment.

- You have reduced skin turgor and are unable to increase your intake of fluids (for example, because of vomiting).

What to Expect at Your Office Visit

The provider will perform a physical exam and ask questions about your medical history, including:

- How long have you had symptoms?

- What other symptoms came before the change in skin turgor (vomiting, diarrhea, others)?

- What have you done to try to treat the condition?

- Are there things that make the condition better or worse?

- What other symptoms do you have (such as dry lips, decreased urine output, and decreased tearing)?

Tests that may be performed:

- Blood chemistry (such as a chem-20)

- CBC

- Urinalysis

You may need intravenous fluids for severe fluid loss. You may need medicines to treat other causes of poor skin turgor and elasticity.

Gallery

References

Ball JW, Dains JE, Flynn JA, Solomon BS, Stewart RW. Skin, hair, and nails. In: Ball JW, Dains JE, Flynn JA, Solomon BS, Stewart RW, eds. Seidel's Guide to Physical Examination. 10th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2023:chap 9.

Greenbaum LA. Deficit therapy. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 70.

McGrath JL, Bachmann DJ. Vital signs measurement. In: Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW, eds. Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 1.

Van Mater HA, Rabinovich CE. Scleroderma and Raynaud phenomenon. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 185.