Age of woman’s first menstruation may signal higher risk of heart disease, UF Health research finds

It might seem like an irrelevant question for a cardiologist to ask a female patient, but University of Florida Health researcher Carl J. Pepine, M.D, hopes it will one day become as routine as asking someone if they smoke or have high blood pressure.

“At what age did you begin menstruating?”

The answer could provide insight into a woman’s risk of heart disease.

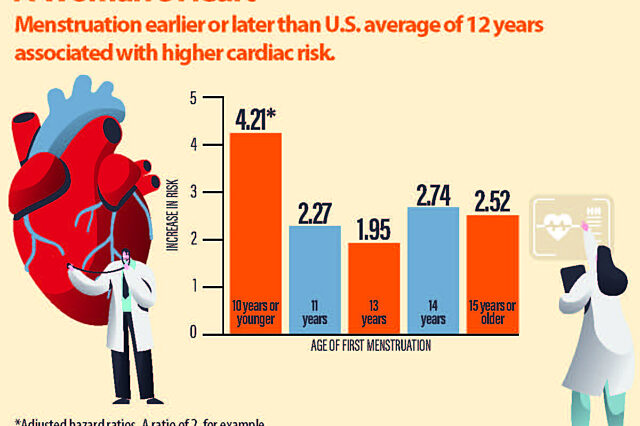

Women who experienced their first menstruation at an early or late age have an elevated risk of developing “major adverse cardiac events,” according to recent research co-authored by Pepine with collaborators at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. These include heart attack, stroke, heart failure and death.

Their study found that women whose first menstruation, called menarche, was at age 10 or younger had a four-fold higher risk of adverse cardiac events. That is compared with those whose menarche occurred at the U.S. average — age 12. For women whose menarche came at age 15 or later, the risk was elevated two-and-a-half times.

In fact, the numbers suggest the risk of cardiac problems for these women might be higher than for other typical risk factors such as high blood pressure or cholesterol, said Pepine.

Women whose menarche occurred at ages 11, 13 or 14 also faced at least a two-fold increased risk of heart problems, according to the research, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

“This is a real hazard,” said Pepine, a professor in the UF College of Medicine’s division of cardiovascular medicine. “This will prompt attention to a novel risk factor that most physicians are not aware of. We hope it will rekindle interest in collecting this information when a woman visits her cardiologist.”

Why menarche has a role in cardiovascular disease risk, Pepine said, still remains unclear, although one hypothesis is focused on genetic variables.

The research involved 648 women enrolled in the National Institutes of Health-funded Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation, or WISE, study, a multicenter collaboration begun in 1997 to examine gender differences in heart disease. Participants, who were tracked for about six years, had symptoms of heart disease serious enough to require a coronary angiography, a test to determine if blood flow to the heart is restricted. Their median age was 57 years.

Critically, the study noted the correlation regardless of a woman’s lifetime exposure to estrogen. Estrogen had long been viewed as being protective of the heart. Research in the last decade or so has cast some doubt on that idea.

“I believe that the findings here are going to help shift people away from this estrogen hypothesis and move toward other things,” Pepine said.

While previous research has noted a connection between age of first menstruation and risk of heart disease, Pepine said this might be the first to incorporate lifetime estrogen exposure levels and is more comprehensive than prior reports. Menarche is marked by rising estrogen levels.

Pepine said it is critical for cardiologists to treat both early and late menarche as an independent risk factor for heart disease and to ask women about age of menarche.

Clinicians don’t generally pay attention to these historical facts in women,” Pepine said.

Heart disease resists a one-size-fits-all mentality, Pepine said. In previous decades, it was generally assumed that symptoms and risk factors of heart disease were the same in both sexes, and women were typically underrepresented in heart research.

Heart disease, he said, has been underdiagnosed and undertreated in women because of the failure to recognize sex-specific differences in cardiovascular disease.

For one thing, women are much less likely to have obstructive coronary artery disease. Instead, reduced blood flow to the heart, a condition called ischemia, more often is a result of problems with the smaller coronary blood vessels or the lining of the coronary arteries in women.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in women with 400,000 deaths annually in the United States. That’s 1-in-3 deaths. Yet, despite increased clinical awareness and advances in research, the study said, “a gap still remains in understanding and effectively recognizing sex-specific risks of preventable” cardiovascular disease.

“This study adds to the concept that, in general, we do not look at women-specific risk factors enough,” said cardiologist Ki Park, M.D., an assistant professor in the division of cardiovascular medicine in the UF College of Medicine. Park was not involved in Pepine’s research. “Cardiologists generally don’t take any type of obstetric or gynecologic history at all.”

Symptoms of heart disease in women tend to manifest themselves differently than in men, Park said. “A significant number of women don’t have the same classic symptoms as men, so they tend to get underdiagnosed and undertreated,” she said.

Women might have more upper abdominal discomfort as a precursor to a heart attack. They also will sometimes have neck or jaw discomfort, compared with the characteristic mid-chest discomfort in men, Park said.

“Sometimes women don’t have any chest discomfort at all,” she said. “They may just have nausea and extreme fatigue.”

If someone knows their age of first menstruation puts them at higher risk of heart disease, then they might, in consultation with their doctor, address the issue in the same way as a patient with diabetes or high blood pressure.

Should they lose weight and regularly schedule visits to a cardiologist to monitor potential heart trouble? Might they increase their exercise regimen?

“Women will ask if they need to be monitored a little more closely,” Pepine said. “Should they perhaps have some other risk factor modifications? As a physician, you’d be much less likely to disregard somebody’s borderline blood pressure reading if you know their menarche was at age 10.”

About the author