Discovery shows how pervasive Epstein-Barr virus could be thwarted

New, early findings by University of Florida Health researchers show how the Epstein-Barr virus’s advance could be thwarted.

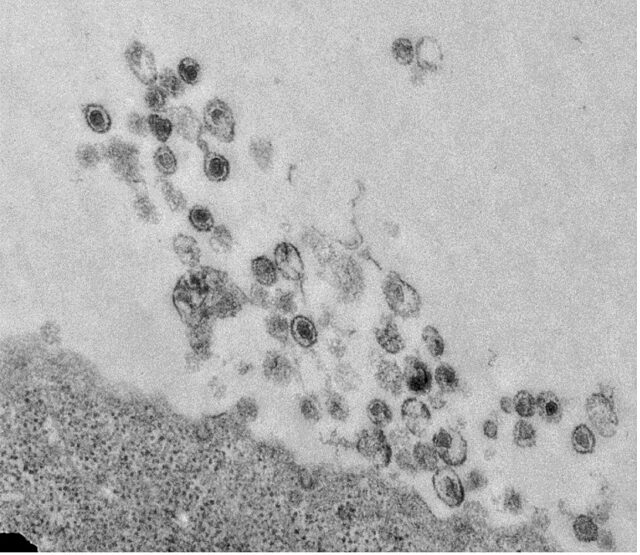

For millions, the Epstein-Barr virus is a lifelong lurker. It can sit dormant for years, sometimes flaring up to cause cancers of the immune system or other serious diseases. To launch its attacks, the virus spreads by hijacking certain genetic machinery.

The researchers focused on the precise moment when the virus pivots from transcribing its genetic sequence and begins replicating. Stopping that sequential process can end its ability to proliferate, they found.

The research sheds new light on longtime questions about how the Epstein-Barr virus and other similar herpesviruses replicate, said Sumita Bhaduri-McIntosh, M.D., Ph.D., a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases in the UF College of Medicine’s department of pediatrics and a member of the UF Health Cancer Center. The findings were published recently in the journal Nucleic Acids Research.

“If that transition within the virus’s genome doesn’t occur smoothly and efficiently, the virus cannot replicate itself. And if it cannot replicate itself, that’s a dead end. Interfering with that process may ultimately be beneficial for preventing or treating diseases,” Bhaduri-McIntosh said.

The findings also have potentially broad implications: Over 90% of people worldwide are infected with the Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It has been linked to a host of diseases, including mononucleosis, multiple sclerosis and viral meningitis, an inflammation of the areas around the brain and spinal cord. Most people contract EBV as children but don’t have any symptoms. No vaccine or treatment exists for EBV.

To establish their findings, the researchers studied the “handoff” in which the virus stops copying its genetic code and begins replicating. They discovered there are five enzymes — proteins that aid chemical reactions in cells — that are crucial to the process. Breaking the virus’s control of that handoff may prove to be the “sweet spot” scientists need to stop EBV from replicating, Bhaduri-McIntosh said.

Because herpesviruses share some common genetic properties, Bhaduri-McIntosh expects the findings could have potential implications for other types of infections. More research is needed to demonstrate that, she said.

The current discovery was bolstered by Michael T. McIntosh, Ph.D., an associate professor of pediatrics. His large-scale analysis of the areas where DNA replication takes place and hundreds of relevant proteins helped the research team focus its attention on proteins of interest.

With no anti-EBV agents or vaccines currently available, identifying the mechanisms that let the virus replicate is key to discovering future therapies, the researchers wrote. Funding for the research was provided by Children’s Miracle Network and the National Institutes of Health.

“This mechanism helps us understand how the virus gets past a critical barrier. Now, we can better understand how it is able to replicate, spread from host to host and cause disease,” Bhaduri-McIntosh said.

About the author