Existing drugs may thwart kidney stone development, UF Health study finds

For people with kidney stones, relief from the searing pain can be short-lived: Between 30% and 50% of patients develop another one. A future solution, however, might already be sitting in many medicine cabinets.

Some medications already in widespread use for other conditions should be further studied for kidney stone prevention, two University of Florida Health researchers have concluded. Their paper reviewed an array of studies that tested some drugs’ effectiveness against recurring calcium kidney stones. They include the cholesterol-reducing medication atorvastatin and a pair of high-blood pressure drugs (losartin and lisinopril), as well as two other medications and a plant-based supplement.

Using data from published animal studies and epidemiological studies in humans, the researchers said there is potential value in repurposing some drugs as a secondary therapy for kidney stone disease.

“When you consider the basic science mechanisms that drive stone formation, statins not only reduce cholesterol but are also potential antioxidants that can decrease kidney inflammation. This is an established approach to improving kidney stone disease,” said Benjamin K. Canales, M.D., a professor in the College of Medicine’s department of urology.

Fully defining the role some medications could play in reducing kidney stone recurrence, however, can be quite challenging, Canales said. That’s because many factors and events affect the formation of kidney stones, including medications and dietary changes.

“Our review of published data validates what has been observed in laboratory studies — these medications might serve dual purposes in humans,” Canales said.

In their paper, Canales and Saeed R. Khan, Ph.D., an emeritus professor in the department of pathology, immunology and laboratory medicine, propose a broader approach to treating recurring kidney stones. The therapies traditionally used to reduce stone formation — diet, medication and fluid — focus on reducing the concentration of minerals such as calcium and oxalate in the urine. Khan and Canales see value in also targeting the areas where kidney stones form.

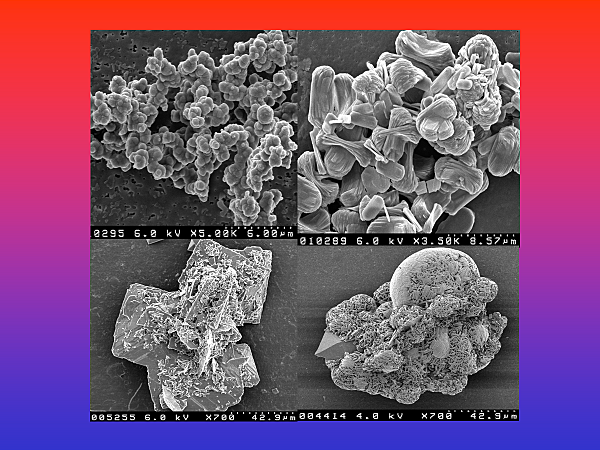

Those areas of the urinary tract, known as plaques and plugs, can be hot spots for kidney stone formation. Canales likens it to the mineral buildup that becomes a pearl after a grain of sand finds its way into an oyster. Balancing urine chemistry is crucial to preventing kidney stones but Canales said focusing on the sites where stones form or collect is also important and worthy of study.

“This is why this type of research is really important. If you can change these conditions deep within the kidneys, you may be able to prevent a stone from ever starting,” he said.

Finding new ways to fight kidney stones is also a demographic imperative, the researchers noted. Cases are rising throughout the world, as is the prevalence of kidney stones among women. The climate in Florida and the rest of the southeastern U.S. also provide a kidney stone incubator: Hot, humid weather leads to more sweating and less urinary volume. That drives up the concentration of ions in urine that leads to kidney stones — earning the region the informal title of the “Stone Belt.”

For now, kidney stone management is limited to medications that alter the chemical content, mineral composition and acidity of a patient’s urine. Adding other medications now used for high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol and other conditions to the mix would require clinical trials and federal regulators’ approval.

Considering the increasing prevalence of kidney stones — and the sometimes debilitating pain they bring — Canales said it’s an intriguing, worthy pursuit.

“If there is a medication that patients are already taking to help their heart disease or cholesterol but it also can help with their stone disease, so much the better,” Canales said.

About the author