UF Health now offers drug that might slow Alzheimer’s disease

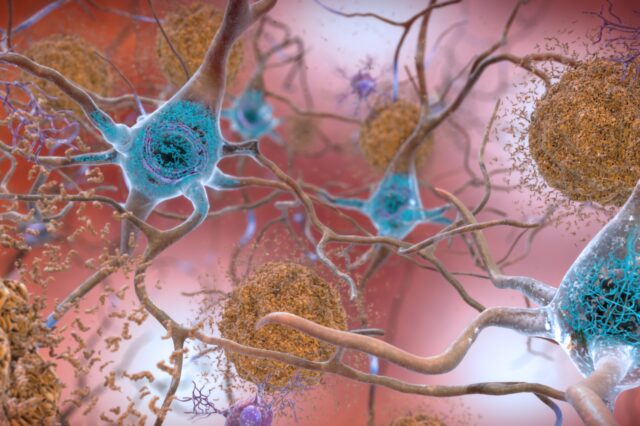

This rendering depicts the accumulation of amyloid plaques near the neurons of the brain. (National Institute on Aging, NIH.)

University of Florida Health is offering a new drug therapy that could temporarily slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in some patients.

Lecanemab is thought to successfully target and eliminate clusters of sticky proteins, or amyloid plaques, that form between the brain’s nerve cells and play an important part in the processes that diminish cognitive function wrought by the disease. The medication was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last year.

“It is the only medication that we have that is disease-modifying,” said Nicholas Doher, D.O., an assistant professor in the UF College of Medicine’s department of neurology who leads UF Health’s efforts with lecanemab. “It’s certainly groundbreaking.”

A study involving a clinical trial with 1,795 patients found that cognitive decline, measured 18 months after the drug was first administered, was 27% lower than in patients who received a placebo. Scientists said the drug is not a cure, but the delay might give patients extra quality time with loved ones. Doctors will learn more about the drug’s effectiveness as more patients are treated.

The drug’s development is important, as numerous previous clinical trials with other drugs targeting the plaques have failed.

Lecanemab is manufactured by the Japanese pharmaceutical company Eisai and its U.S. partner Biogen. They market the product under the brand name Leqembi, which is also the generic name.

Doher said the treatment is available through Medicare, and private health insurers usually follow its lead, though patients need to verify coverage.

While the drug offers hope in the battle against a disease that has been stubborn in yielding its secrets, Doher cautioned that not all patients will be eligible.

For one thing, those whose disease is too advanced do not seem to benefit, he said. Only those with mild cognitive impairment to mild dementia are eligible. Amyloid plaques must nonetheless be present since that is the drug’s target. Additionally, genetic testing is strongly recommended to reveal factors that could increase the risk of side effects associated with the medication.

Also, a patient must have a family member who can monitor and assist them during the long treatment period, which includes a drug infusion every two weeks.

“It takes a level of commitment from the patient and their care partner,” Doher said. “It means receiving multiple infusions, tests and follow-up appointments. That’s not for everybody.”

Lecanemab is a monoclonal antibody. These are molecules created in the laboratory that, when introduced into the body, are designed to modify or mimic the immune system’s fight against dangerous cells. They have been used to battle COVID-19 and cancer, among other applications.

“It’s telling the immune system to go into the brain and target these plaques,” Doher said.

Most patients, he said, do well on the medication with limited complications. Physicians, however, must monitor them with periodic MRIs for potentially serious adverse reactions, such as brain inflammation and bleeding.

It is unclear whether infusions every two weeks will be required indefinitely once amyloid plaques are no longer detectable. Researchers believe the disease might continue to advance even in their absence.

How long patients might receive infusions of the drug isn’t clear. While the clinical trial monitored patients for 18 months, the treatment period presumably could be extended as long as lecanemab remains effective, Doher said.

“I think lecanemab affirms that plaques are driving Alzheimer’s disease in some way, though it is also clear that other factors play a role,” Doher said. “This drug can provide a meaningful benefit, although it is small at this time.”

About the author