Impetigo

Definition

Impetigo is a common skin infection.

Alternative Names

Streptococcus - impetigo; Strep - impetigo; Staph - impetigo; Staphylococcus - impetigo

Causes

Impetigo is caused by streptococcus (strep) or staphylococcus (staph) bacteria. Methicillin-resistant staph aureus (MRSA) is an increasing cause.

Skin typically has many types of bacteria on it. When there is a break in the skin, bacteria can enter the body and grow there. This causes inflammation and infection. Breaks in the skin may occur from injury or trauma to the skin or from insect, animal, or human bites.

Impetigo may also occur on the skin, where there is no visible break.

Impetigo is most common in children who live in unhealthy conditions.

In adults, it may occur following another skin problem. It may also develop after a cold or other virus.

Impetigo can spread to others. You can catch the infection from someone who has it if the fluid that oozes from their skin blisters touches an open area on your skin.

Symptoms

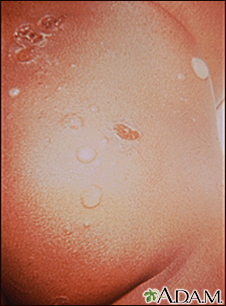

Symptoms of impetigo are:

- One or many blisters that are filled with pus and easy to pop. In infants, the skin is reddish or raw-looking where a blister has broken.

- Blisters that itch are filled with yellow or honey-colored fluid and ooze and crust over. Rash that may begin as a single spot but spreads to other areas due to scratching.

- Skin sores on the face, lips, arms, or legs that spread to other areas.

- Swollen lymph nodes near the infection.

- Patches of impetigo on the body (in children).

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will look at your skin to determine if you have impetigo.

Your provider may take a sample of bacteria from your skin to grow in the lab. This can help determine if MRSA is the cause. Specific antibiotics are needed to treat this type of bacteria.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to get rid of the infection and relieve your symptoms.

Your provider will prescribe an antibacterial cream. You may need to take antibiotics by mouth if the infection is severe.

Gently wash (Do not scrub) your skin several times a day. Use an antibacterial soap to remove crusts and drainage.

Outlook (Prognosis)

The sores of impetigo heal slowly. Scars are rare. The cure rate is very high, but the problem often comes back in young children.

Possible Complications

Impetigo may lead to:

- Spread of the infection to other parts of the body (common)

- Kidney inflammation or failure (rare)

- Permanent skin damage and scarring (very rare)

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have symptoms of impetigo.

Prevention

Prevent the spread of infection.

- If you have impetigo, always use a clean washcloth and towel each time you wash.

- Do not share towels, clothing, razors, and other personal care products with anyone.

- Avoid touching blisters that are oozing.

- Wash your hands thoroughly after touching infected skin.

Keep your skin clean to prevent getting the infection. Wash minor cuts and scrapes well with soap and clean water. You can use a mild antibacterial soap.

Gallery

References

Dinulos JGH. Bacterial infections. In: Dinulos JGH, ed. Habif's Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 9.

Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM. Cutaneous bacterial infections. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 685.

Pasternack MS, Swartz MN. Cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and subcutaneous tissue infections. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 93.