Peripheral intravenous line - infants

Definition

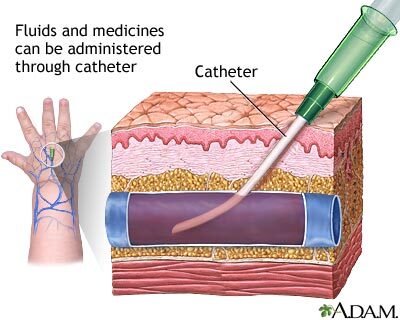

A peripheral intravenous line (PIV) is a tiny, short, flexible tube, called a catheter. A health care provider puts the PIV through the skin into a vein in the scalp, hand, arm, or foot. The PIV can be attached to longer tubing to give medicine or fluids through the vein. This article addresses PIVs in babies.

Alternative Names

PIV - infants; Peripheral IV - infants; Peripheral line - infants; Peripheral line - neonatal

Information

WHY IS A PIV USED?

A provider uses the PIV to give fluids or medicines to a baby.

HOW IS A PIV PLACED?

Your provider will:

- Clean the skin.

- Stick the small catheter with a needle on the end through the skin into the vein.

- Once the PIV is in the proper position, the needle is taken out. The catheter stays in the vein.

- The PIV is connected to a small plastic tube that connects to an IV bag.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF A PIV?

PIVs can be hard to place in a baby, such as when a baby is very chubby, sick, and/or small. In some cases, the provider cannot put in a PIV. If this happens, another therapy is needed.

PIVs may stop working after only a short time. If this happens, the PIV will be taken out and a new one will be put in.

If a PIV slips out of the vein, fluid or medicine can go into the skin instead of the vein. When this happens, the IV is considered "infiltrated." The IV site will look puffy and may be red. Sometimes, an infiltrate may cause the skin and tissue to get very irritated. The baby can get a tissue burn if the medicine that was in the IV is irritating to the skin. In some special cases, a counteracting medicine may be injected into the skin to help prevent long-term skin damage from an infiltrate.

When a baby needs IV fluids or medicine over a long period of time, a midline catheter or PICC is used. Regular IVs only last 1 to 3 days before needing to be replaced. A midline or PICC can stay in for 2 to 3 weeks or longer.

Gallery

References

Center of Disease Control and Prevention website. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections, 2011. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/BSI/index.html. Accessed January 24, 2022.

Santillanes G, Claudius I. Pediatric vascular access and blood sampling techniques. In: Roberts J, ed. Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 19.