Augmenting Cognitive Training in Older Adults: The “ACT Study”

Have you sometimes forgotten a phone number, walked to another room to complete an errand but forgotten what it was while walking, or failed to notice a car approaching until it was right next to you? Occasional lapses in memory and attention may not seem significant when we’re young, but we might wonder about the implications of such lapses as we age, and about whether we can do anything to minimize them.

In the normal course of aging, about 40 percent of individuals 65 or older have age-associated memory loss. Normal aging is also associated with steady reductions in attention, speed of processing and complex reasoning. Only about 1 percent of adults will go on to develop dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, each year. But what about the vast majority of older adults who experience changes in mental functioning that may, even without dementia, come to adversely affect their everyday functioning and independence? Is there a way to mitigate this age-associated process? Could this help to slow or prevent dementia onset?

A few weeks ago, the National Institute on Aging announced that it would fund a UF grant application that would test the efficacy of certain methods designed to slow the process of age-associated memory loss and potentially prevent onset of dementia. This 5-year, $5.7 million grant is titled Augmenting Clinical Training in Older Adults: The “ACT Study.” The lead principal investigator is Adam Woods, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the department of aging and geriatric research at UF’s College of Medicine and assistant director of the Cognitive Aging and Memory Clinical Translational Research Program, known as CAM-CTRP. He is joined by two other PIs: Michael Marsiske, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of clinical and health psychology at UF’s College of Public Health and Health Professions, and Ronald Cohen, Ph.D., professor and Evelyn F. McKnight chair for clinical translational research in cognitive aging and director of the CAM-CTRP.

The story of this grant is, I believe, a good subject for OTSP for several reasons: The topic is of general interest; the PIs brought different scientific backgrounds and perspectives to the study; and the grant is a wonderful example of how “The Power of Together” plays out in the research arena, with philanthropy stimulating interest in a research question that brings together a variety of faculty, centers and institutes at UF and two other universities.

Some of the reasons for age-associated memory loss involve:

- Age-related decline in frontal brain regions undermine not only memory function, but a wide variety of cognitive domains implicated in cognitive aging.

- Hormones and proteins that protect and repair brain cells and stimulate neural growth might also decline with age.

- Older people can experience decreased blood flow to the brain for a variety of reasons, which can impair memory and problem solving, and can lead to changes in everyday cognitive skills.

On the other hand, the brain is capable of producing new connections between brain cells at any age, a process referred to as “neuroplasticity,” so significant memory loss may not be an inevitable result of aging. But just as with muscle strength, when it comes to the brain you may have to “use it or lose it.” The ACT study tests whether a novel method of noninvasive brain stimulation that enhances neuroplasticity can augment the beneficial effects of cognitive training to reduce age-associated cognitive decline.

Since 1997, ACT principal investigator Michael Marsiske has been one of the PIs on the NIA-funded ACTIVE multi-site clinical trial. (ACTIVE is the acronym for the “Advanced Cognitive Training in Independent and Vital Elderly” study.) That study, which offered three kinds of cognitive training to adults age 65 and older found that, in a diverse sample (27 percent of participants were African American), training effects were large (comparable to “reversing” seven to 14 years of prior age-related decline), durable (trained participants still outperformed untrained participants a decade later) and generalized to many “real-world” outcomes. Participants who received several of the interventions showed less limitation with activities of daily living, better mood and a greater sense of control. Interestingly, over the course of a decade of follow-up, they were 50 percent less likely to be involved in a motor vehicle crash.

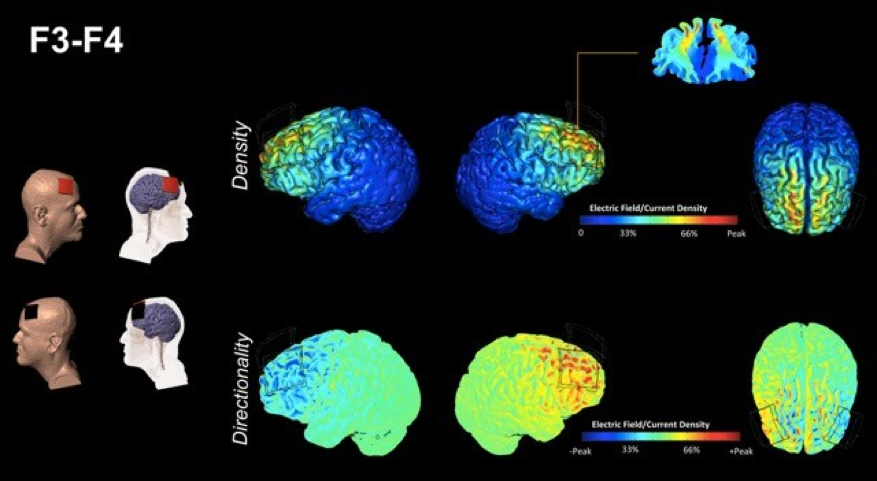

The ACT study leverages this prior work, using technological developments (computer-administered cognitive training) to deliver some of the same interventions that were successful in ACTIVE. However, the main focus of ACT is to test whether the benefits of cognitive training can be augmented by a novel intervention called “transcranial direct current stimulation,” or tDCS. tDCS is a form of noninvasive brain stimulation that uses constant, weak and safe electrical current (e.g., 2 milliamps) delivered to the brain via electrodes placed on the surface of the scalp. This method has primarily been used as a basic science tool for investigating brain-behavior relationships and as a method for facilitating cognitive enhancement, but more recently has shown promise for treatment of patients with depression or chronic pain. The primary mechanism of tDCS involves either increasing or decreasing the neuroplastic response of brain tissue, depending on the stimulation parameters used. Prior work by Dr. Woods demonstrates that neuroplastic effects of tDCS are strongest when stimulation is paired with a challenging learning task. The end result is enhanced speed and quality of learning at both the behavioral and neural level. This means that pairing tDCS with a method that has been shown to combat cognitive aging in older adults (i.e., cognitive training) could hold great promise for in the fight against cognitive aging and dementia. Additionally, the ACT study incorporates state-of-the-art neuroimaging that can help visualize how the brain response reorganizes after training, and whether there is evidence of neural plasticity and brain change.

The ACT study is also innovative in its statistical approach, featuring an “adaptive” randomized clinical trial design. Specifically, an adaptive two-phase randomized clinical trial will be conducted at three sites (UF, the University of Arizona and the University of Miami) to examine the impact of cognitive training versus an education training control condition (Phase 1), and then the impact of cognitive training augmented by tDCS versus a placebo/sham stimulation condition (Phase 2). Participants will consist of 360 elderly men and women 65-89 years of age with evidence of age-related cognitive decline, but without a formal diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. The investigators will compare changes in cognitive and brain function resulting from cognitive training vs. education control, and cognitive training plus tDCS vs. sham stimulation, using a comprehensive neurocognitive, clinical and multimodal neuroimaging assessment of brain structure, function and metabolic state. Use of the adaptive design will allow the trial to focus the majority of its sample size into the intervention question of interest (tDCS benefits) while still collecting critical mechanistic data that helps us understand why tDCS and cognitive training are beneficial in the fight against cognitive aging. In addition to determining whether tDCS augmentation will slow age-associated cognitive decline, one aim of the study will be to learn whether cognitive training, with or without tDCS, can prevent the onset of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. To date, ACT is the largest NIH-funded Phase III clinical trial for tDCS in history.

It is likely that the ACT study would not have been conceptualized or written without the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. This foundation was established by Evelyn F. McKnight in 1999, and is responsible for the gift that named the Evelyn F. and William L. McKnight Brain Institute at the University of Florida. Mrs. McKnight, a nurse, and her late husband, William M. McKnight, long-time chairman of the board of 3M Corp., were interested in the effects of aging on memory. In establishing the MBRF, it was Mrs. McKnight’s intent that it would support scientific research on the understanding and alleviation of age-related memory loss. Funding has now evolved to support McKnight Brain Institutes at four universities, with UF as its flagship. Building on a community of McKnight researchers interested in age-related memory loss and cognitive aging, and to facilitate the recruitment of a diverse group of research participants, the ACT study will also contain recruitment sites at the McKnight Brain Institutes at the University of Miami and the University of Arizona.

While Dr. Marsiske has been at UF since 2000, the MBRF was instrumental in recruiting Dr. Cohen (2012) and Dr. Woods (2013). Building on this philanthropic foundation, and the network of three McKnight Brain Institutes that will participate in the study, the ACT study team is a true example of the Power of Together. In addition to resources from the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, ACT investigators were able to build on the technical expertise and long track record of clinical trials conducted in the UF Institute on Aging, under the directorship of Marco Pahor, M.D. In addition, the three ACT co-principal investigators brought different experiences and scientific perspectives to the study:

Adam Woods, Ph.D., brought forward the concept of augmenting cognitive training with tDCS, having won the Young Investigator Award at the neuromodulation field’s national conference in 2015 (NYC Neuromodulation) for his novel contributions to the science of noninvasive brain stimulation. Adam has been a leader in the field of tDCS for almost a decade. After completing graduate work in cognitive neuroscience at the George Washington University in 2010, he completed a postdoctoral fellowship in noninvasive brain stimulation at the University of Pennsylvania. Over the past 10 years, Adam has contributed field standards papers in technical aspects, application and safety of tDCS in addition to numerous papers on the use of tDCS for cognitive enhancement and an upcoming book titled a “Practical Guide to tDCS.” He is also the founder and director of the only CME-certified tDCS training fellowship and has trained over 500 researchers and clinicians in the context of this fellowship. More recently, Adam received a K01 that dovetails with the aims of ACT, but adds a much-needed investigation of the tDCS-CT dose-response relationship and mechanistic brain changes underlying tDCS benefits. Adam was also the PI of a McKnight Brain Research Foundation endowment funded study in the CAM-CTRP that not only built the infrastructure critical to ACT, but also provided the pilot and feasibility data that were central to ACT being funded. Since arriving at UF, he has focused on the clinical translation of his basic science tDCS work to clinically meaningful application. In his role as assistant director of the CAM-CTRP and director of the CAM Neurophysiology and Neuromodulation Research Core, he has worked to promote both research and clinical translational application of noninvasive brain stimulation at the University of Florida.

Adam Woods, Ph.D., brought forward the concept of augmenting cognitive training with tDCS, having won the Young Investigator Award at the neuromodulation field’s national conference in 2015 (NYC Neuromodulation) for his novel contributions to the science of noninvasive brain stimulation. Adam has been a leader in the field of tDCS for almost a decade. After completing graduate work in cognitive neuroscience at the George Washington University in 2010, he completed a postdoctoral fellowship in noninvasive brain stimulation at the University of Pennsylvania. Over the past 10 years, Adam has contributed field standards papers in technical aspects, application and safety of tDCS in addition to numerous papers on the use of tDCS for cognitive enhancement and an upcoming book titled a “Practical Guide to tDCS.” He is also the founder and director of the only CME-certified tDCS training fellowship and has trained over 500 researchers and clinicians in the context of this fellowship. More recently, Adam received a K01 that dovetails with the aims of ACT, but adds a much-needed investigation of the tDCS-CT dose-response relationship and mechanistic brain changes underlying tDCS benefits. Adam was also the PI of a McKnight Brain Research Foundation endowment funded study in the CAM-CTRP that not only built the infrastructure critical to ACT, but also provided the pilot and feasibility data that were central to ACT being funded. Since arriving at UF, he has focused on the clinical translation of his basic science tDCS work to clinically meaningful application. In his role as assistant director of the CAM-CTRP and director of the CAM Neurophysiology and Neuromodulation Research Core, he has worked to promote both research and clinical translational application of noninvasive brain stimulation at the University of Florida.

Michael Marsiske, Ph.D., has a long history of conducting clinical trials aimed at investigating cognitive interventions in older adults, including the decade-long ACTIVE trial described above. Michael has been involved in cognitive training since his undergraduate work at The University of Toronto, where his honors thesis was a cognitive training study. After doctoral work at Penn State, he did a three-year postdoc at the Max Planck Institute fuer Bildungsforschung in Berlin; both institutions and his mentors are widely regarded as the founders of modern cognitive intervention research for older adults. After starting his academic career at Wayne State University in Detroit, Marsiske joined UF in the department of clinical and health psychology and Institute on Aging. Since 2003, he has served as PI and training director of an NIA-funded T32 program (aimed at training predoctoral fellows in methods for research on aging), and he now also serves as a core leader for the Data Management and Data Analysis Core of the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Michael Marsiske, Ph.D., has a long history of conducting clinical trials aimed at investigating cognitive interventions in older adults, including the decade-long ACTIVE trial described above. Michael has been involved in cognitive training since his undergraduate work at The University of Toronto, where his honors thesis was a cognitive training study. After doctoral work at Penn State, he did a three-year postdoc at the Max Planck Institute fuer Bildungsforschung in Berlin; both institutions and his mentors are widely regarded as the founders of modern cognitive intervention research for older adults. After starting his academic career at Wayne State University in Detroit, Marsiske joined UF in the department of clinical and health psychology and Institute on Aging. Since 2003, he has served as PI and training director of an NIA-funded T32 program (aimed at training predoctoral fellows in methods for research on aging), and he now also serves as a core leader for the Data Management and Data Analysis Core of the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

Ron Cohen, Ph.D., is an international leader in the fields of neuropsychology and human neuroscience. He is widely recognized for his studies employing contemporary neuroscience methods to understand how aging and associated diseases (e.g., hypertension, heart disease, obesity, HIV) affect brain aging. He serves as director of the CAM-CTRP and the Evelyn F. McKnight Chair for Clinical Translational Research in Cognitive Aging at the University of Florida, both of which are endowed by the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. His research focuses on age-associated changes in memory, cognition, and behavior, as well as alterations in brain structure and function. A major line of his research concerns comorbidities that contribute to cognitive and brain aging: heart disease and cerebral hemodynamic function, obesity and metabolic disturbances, HIV, and heavy alcohol use. Dr. Cohen oversees a multidisciplinary research program that integrates neurocognitive, neuroimaging, and laboratory biomarker methods. He has a two decade-long history of continuous NIH-supported studies of age-associated brain disorders linked to various etiologies that employ functional and structural neuroimaging. In addition to numerous peer-reviewed publications, he authored “Neuropsychology of Attention,” the first book on this topic, published as a second edition last year. He also was editor of “Brain Imaging in Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Neuroscience.” Dr. Cohen will oversee neuroimaging on the ACT trial and as CAM-CTRP director will maintain integration and communication across the three ACT research sites.

Ron Cohen, Ph.D., is an international leader in the fields of neuropsychology and human neuroscience. He is widely recognized for his studies employing contemporary neuroscience methods to understand how aging and associated diseases (e.g., hypertension, heart disease, obesity, HIV) affect brain aging. He serves as director of the CAM-CTRP and the Evelyn F. McKnight Chair for Clinical Translational Research in Cognitive Aging at the University of Florida, both of which are endowed by the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. His research focuses on age-associated changes in memory, cognition, and behavior, as well as alterations in brain structure and function. A major line of his research concerns comorbidities that contribute to cognitive and brain aging: heart disease and cerebral hemodynamic function, obesity and metabolic disturbances, HIV, and heavy alcohol use. Dr. Cohen oversees a multidisciplinary research program that integrates neurocognitive, neuroimaging, and laboratory biomarker methods. He has a two decade-long history of continuous NIH-supported studies of age-associated brain disorders linked to various etiologies that employ functional and structural neuroimaging. In addition to numerous peer-reviewed publications, he authored “Neuropsychology of Attention,” the first book on this topic, published as a second edition last year. He also was editor of “Brain Imaging in Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Neuroscience.” Dr. Cohen will oversee neuroimaging on the ACT trial and as CAM-CTRP director will maintain integration and communication across the three ACT research sites.

At its core, the ACT trial addresses the question of whether cognitive training combined with transcranial direct current stimulation not only boosts the mental performance of older adults, but does so beyond the strong effects already seen with cognitive training alone. This study will provide definitive insight into the value of combating cognitive decline in a rapidly aging U.S. population using tDCS with cognitive training. And it couldn’t have been done without the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, the Institute on Aging, the presence of a long-standing investigator already at UF, and the addition in recent years of new faculty interested in cognitive aging who brought different experiences and perspectives.

The Power of Together,

David S. Guzick, M.D., Ph.D. Senior Vice President for Health Affairs, UF President, UF Health

About the author