Search for a major depression trigger reveals a familiar face: Discovery opens new possibilities for treatments

JUPITER, Fla.— A common amino acid, glycine, can deliver a “slow-down” signal to the brain, likely influencing major depression, anxiety and other mood disorders in some people, scientists at The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute for Biomedical Innovation & Technology report online in the journal Science today.

The discovery improves understanding of the biological causes of major depression and could accelerate efforts to develop new, faster-acting medications for such hard-to-treat mood disorders, said neuroscientist Kirill Martemyanov, Ph.D., corresponding author of the study, appearing in Friday’s edition of Science magazine.

“There are limited medications for people with depression,” said Martemyanov, who chairs the neuroscience department at the institute. “Most of them take weeks before they kick in, if they do at all. New and better options are really needed.”

Major depression is among the world’s most urgent health needs. Its numbers have surged in recent years, especially among young adults. As depression’s disability, suicide numbers and medical expenses have climbed, a study by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021 put its economic burden at $326 billion annually in the United States.

Martemyanov said he and his team of students and postdoctoral researchers have spent many years working toward this discovery. They didn’t set out to find a cause, much less a possible treatment route for depression. Instead, they asked a basic question: How do sensors on brain cells receive and transmit signals into the cells, and then change the cells’ activity? Therein lay the key to understanding vision, pain, memory, behavior and possibly much more, Martemyanov suspected.

“It’s amazing how basic science goes. Fifteen years ago we discovered a binding partner for proteins we were interested in, which led us to this new receptor,” Martemyanov said. “We’ve been unspooling this for all this time.”

In 2018 the Martemyanov team found the new receptor was involved in stress-induced depression. If mice lacked the gene for the receptor, called GPR158, they proved surprisingly resilient to chronic stress.

That offered strong evidence that GPR158 could be therapeutic target, he said. But what sent the signal?

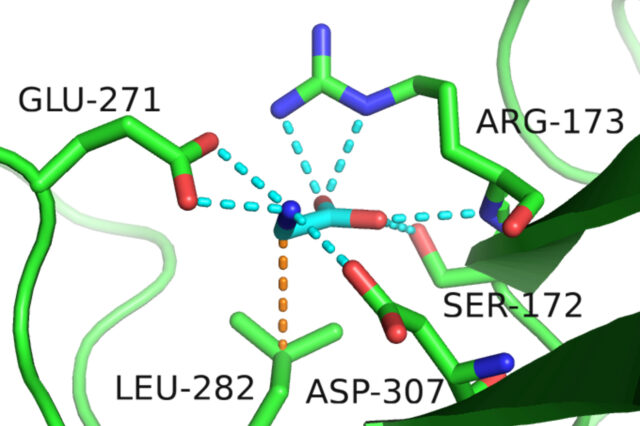

A breakthrough came in 2021, when his team solved the structure of GPR158. What they saw surprised them. The GPR158 receptor looked like a microscopic clamp with a compartment — akin to something they had seen in bacteria, not human cells.

“We were barking up the completely wrong tree before we saw the structure,” Martemyanov said. “We said, ‘Wow, that’s an amino acid receptor. There are only 20, so we screened them right away and only one fit perfectly. That was it. It was glycine.”

That wasn’t the only odd thing. The signaling molecule was not an activator in the cells, but an inhibitor. The business end of GPR158 connected to a partnering molecule that hit the brakes rather than the accelerator when bound to glycine.

“Usually receptors like GPR158, known as G protein coupled receptors, bind G proteins. This receptor was binding an RGS protein, which is a protein that has the opposite effect of activation,” said Thibaut Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher from Martemyanov’s group and first author of the study.

“Usually receptors like GPR158, known as G protein coupled receptors, bind G proteins. This receptor was binding an RGS protein, which is a protein that has the opposite effect of activation,” said Thibaut Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher from Martemyanov’s group and first author of the study.

Scientists have been cataloging the role of cell receptors and their signaling partners for decades. Those that still don’t have known signalers, such as GPR158, have been dubbed “orphan receptors.”

The finding means that GPR158 is no longer an orphan receptor, Laboute said. Instead, the team renamed it mGlyR, short for “metabotropic glycine receptor.”

“An orphan receptor is a challenge. You want to figure out how it works,” Laboute said. “What makes me really excited about this discovery is that it may be important for people’s lives. That’s what gets me up in the morning.”

Glycine itself is sold as a nutritional supplement billed as improving mood. It is a basic building block of proteins and affects many different cell types, sometimes in complex ways. In some cells, it sends slow-down signals, while in other cell types, it sends excitatory signals. Some studies have linked glycine to the growth of invasive prostate cancer.

More research is needed to understand how the body maintains the right balance of mGlyR receptors and how brain cell activity is affected, he said. He intends to keep at it.

“We are in desperate need of new depression treatments,” Martemyanov said. “If we can target this with something specific, it makes sense that it could help. We are working on it now.”

The study, “Orphan receptor GPR158 serves as a metabotropic glycine receptor: mGlyR,” appears Friday, March 31, in the journal Science.

In addition to Laboute and Martemyanov, the authors are Dipak Patil, Ph.D., formerly a staff scientist in Martemyanov lab, now with Eli Lilly and Company; Staff Scientist Stefano Zucca, Ph.D.; graduate student Brittany Wheatley, and Assistant Research Professor Raktim Roy, Ph.D., all of The Wertheim UF Scripps Institute. Other contributors are Associate Professor Stefano Forli, Ph.D., postdoctoral researcher Matthew Holcomb, Ph.D.; and graduate student Chris Garza, all of Scripps Research in La Jolla, California.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01MH105482 and R01GM069832. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: Laboute and Martemyanov are listed as inventors on a patent application describing methods to study GPR158 activity. Martemyanov is a cofounder of Blueshield Therapeutics, a startup company pursuing GPR158 as a drug target.

Media Contact: Stacey DeLoye, 561-228-2551, s.deloye@ufl.edu